Inequalities in mental health, well-being and wellness in Canada

Trends in mental health inequalities in Canada. Highlights changes over time and drivers of mental health inequalities.

- Last updated: 2024-09-10

On this page

Methods

Exploratory Sequential Evidence Synthesis

This report employs evidence synthesis—the integration of diverse research findings or data to generate a consolidated summary of evidence—informed by exploratory sequential approach to provide a more nuanced understanding of mental health inequalities in Canada, including their structural and societal drivers, and how they have changed over time. In the following sections we describe the rapid review process utilized to gather qualitative studies and the quantitative trend analyses conducted. The sequential nature of these analyses, particularly the literature reviews, allowed us to iteratively refine this report and the knowledge it captured through the quantitative trend analyses. By taking an exploratory approach to our qualitative and quantitative evidence synthesis, we integrated diverse data sources, creating a more holistic understanding of mental health inequalities in Canada Footnote 1 . The purpose of including this type of approach was to first capture the circumstances and contexts that impact mental health outcomes with the aim of informing what needs to be explored by quantitative analysis. The insightful evidence from qualitative research combined with population-level trends provides a more nuanced understanding than those explored to date. An exploratory sequential approach such as this has been applied to build comprehensive understandings of interventions in health systems Footnote 1 . Public health issues, like those presented in this report, are complex in nature and the combined utilization of qualitative and quantitative data together helps in making evidence-informed decisions Footnote 2 Footnote 3 .

Qualitative Literature Review

Objective

This rapid literature review aimed to synthesize qualitative research of mental health inequalities in Canada over a ten-year period (2012 – 2022) and to provide possible explanations of how some social determinants contribute to inequalities in mental health.

Specifically, the qualitative review initially sought to map the current landscape of mental health inequalities guided by the following questions:

1. How are “mental health” and “mental health inequalities” conceptualized in Canada?

2. What are the social determinants of mental health in Canada and why does equity matter?

3. How have mental health inequalities changed over time in Canada, and for whom?

We employed a staged and iterative process of narrative and framework syntheses to explore the topic of mental health inequalities in Canada. We began the review with the goal of mapping topics, subpopulations, theoretical perspectives and policies or legislation referred to in the studies. Given the volume of studies reviewed and the array of topics covered, we first attempted to apply a deductive approach by utilizing a framework synthesis to organize findings by 1) sex/gender, 2) age, 3) marital status, 4) immigration status, 5) Indigenous identity, 6) race/ethnicity, 7) educational attainment, 8) income, 9) employment status, 10) housing ownership status and 11) sense of community belonging. Due to the intersectional nature of the studies, this type of synthesis proved restrictive and instead conducted a narrative synthesis to “generate new insights or knowledge by transparently bringing together existing research findings” (Mays & Pope, 2020). To test for potential bias in terms of the key emerging topics, we conducted a supplementary search by sampling and reviewing qualitative research to ensure that these themes were consistent with systematic reviews of social determinants of mental health beyond the ten years search time frame of 2012-2022. The supplementary search on google scholar used key words such as social determinants, mental health, Canada and systematic review. The first 100 searches were reviewed, where search results were from 1999 and onwards to find any relevant systematic reviews. Four relevant systematic reviews were found, where the full text was reviewed to extract all key themes. It was found that all themes discussed in this narrative synthesis were consistent with key themes emerging prior to the search time frame.

Search Strategy

A Health Canada librarian compiled three different searches as our parameters evolved. We proceeded with a first search selecting a ten-year period (2012 – 2022) to be relevant to the current social and economic contexts and the most up-to-date literature that also covered the COVID-19 pandemic period. Three databases were searched to find relevant studies: Ovid MEDLINE, APA PsycInfo and Embase. The search topics were: 1) Qualitative mental health inequalities and social determinants of health studies, 2) COVID-19, mental health inequalities and social determinants.

Study Eligibility

To be included, the literature had to be 1) using any type of qualitative methodology in data collection and analysis 2) pertinent to understanding inequalities in mental health, 3) conducted in Canada, 4) published between 2012 – 2022. An iterative process was used to ensure that articles were relevant to our overall research questions. More details on the inclusion criteria are below in Table 1. Excluded studies were quantitative, mixed-methods, commentaries, editorials, conference abstracts, systematic reviews, scoping reviews and dissertations, interventions clinical practice guidelines, studies focused on health care provider perspectives and research examining reliability and validity of psychological or cognitive assessment tools.

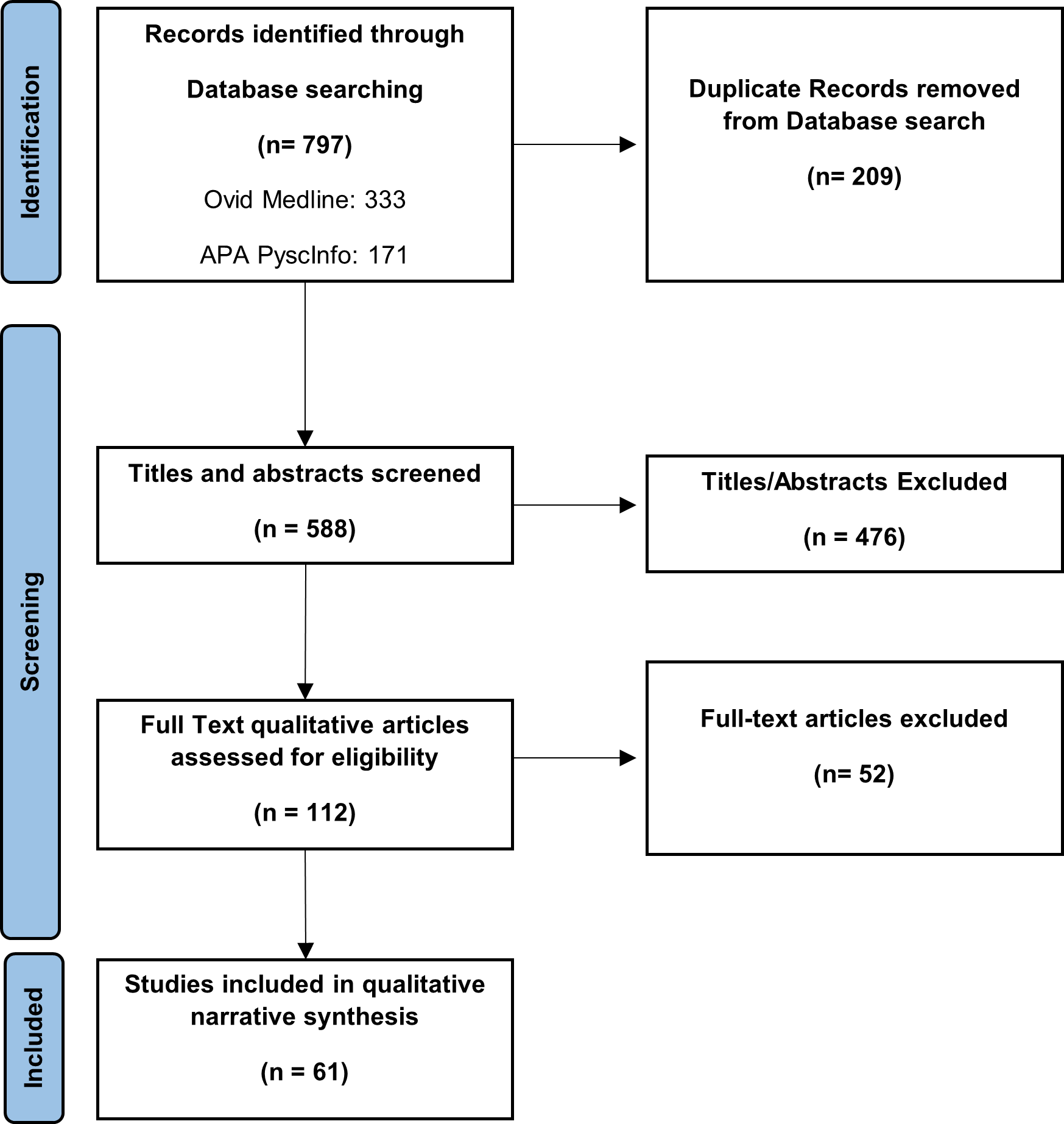

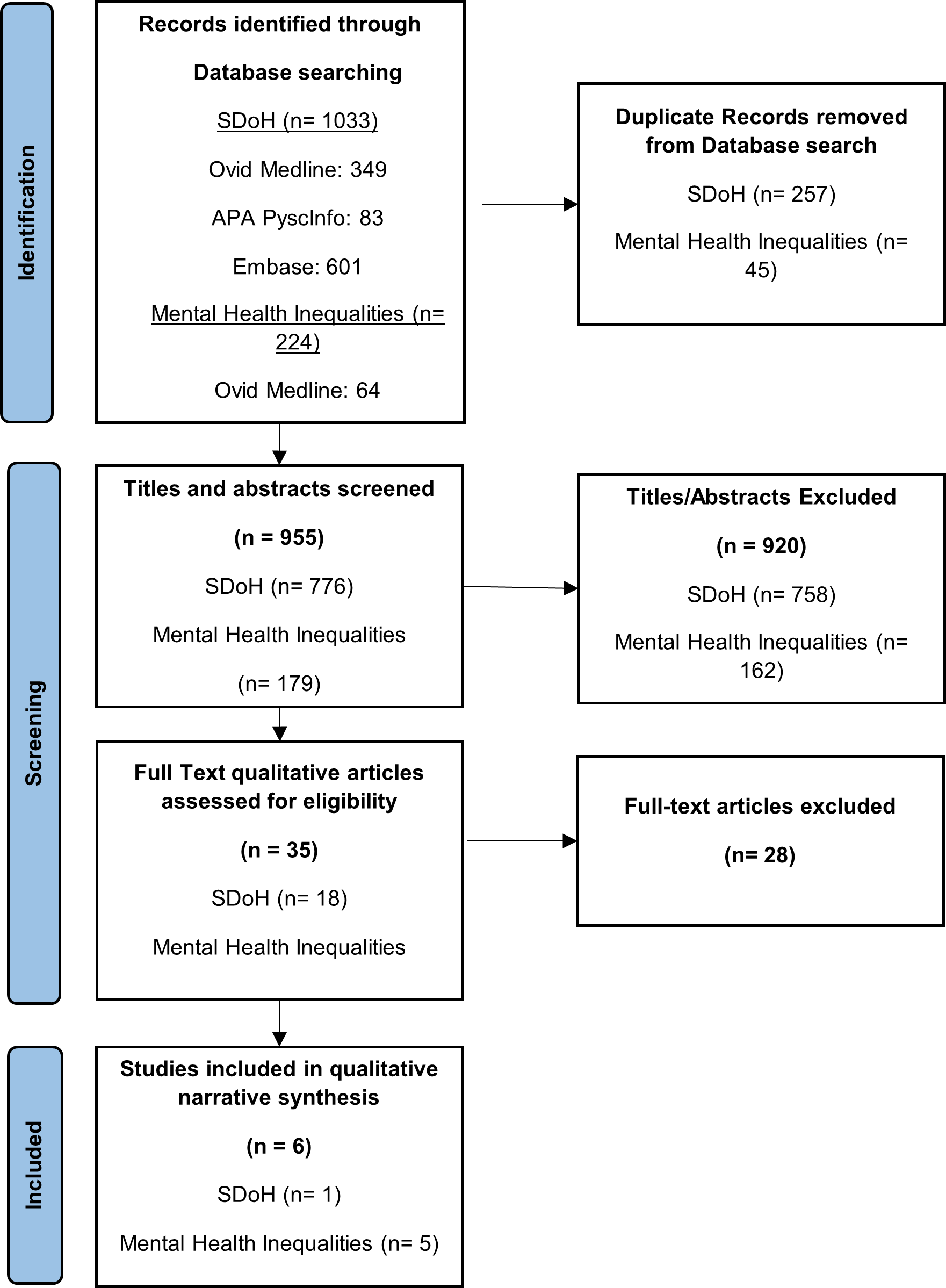

We employed a similar screening process for the two sets of searches, title and abstract screening, blind review of 10% of total articles, 90% agreement discussion and resolution of disagreements, and screening of remainder of studies by primary reviewer. Details of the screening processes can be seen below in Figures 1 and 2.

Selection

From the first search, a total of 588 peer-reviewed studies were identified through title and abstract screening, 112 were reviewed for full-text screening and resulted in 61 studies selected. In the second search, 955 studies were identified through title and abstract screening, 35 were reviewed for full-text screening and resulted in 6 studies selected. A total of 67 pieces of literature were included in the narrative synthesis.

Figure 1. Flow Chart for qualitative mental health studies

Figure 1: Text description

- Identification:

- 797 studies identified through database searching (Ovid Medline and APA PsycINFO).

- 209 duplicate studies removed from database search.

- Screening:

- 588 studies screened for titles and abstracts.

- 476 studies screened based on title and abstract.

- 112 full text qualitative articles assessed for eligibility.

- 52 full-text articles excluded (e.g., irrelevant, non-English, non-French, etc.).

- Inclusion:

- 61 studies included in qualitative synthesis.

Figure 2. Flow Chart for COVID-19 qualitative mental health studies

Figure 2: Text description

This PRISMA Plus flow diagram outlines the stages of the rapid literature review process, including identification, screening, and inclusion. The diagram provides a visual representation of how studies were filtered at each stage.

- Identification:

- 1033 studies identified related to Social Determinants of Health through database searching (Ovid Medline, APA PsycINFO, Embase).

- 224 studies identified related to Mental Health Inequalities through database searching (Ovid Medline, APA PsycINFO, Embase).

- 257 Social Determinants of Health studies removed as duplicates.

- 45 Mental Health Inequalities studies removed as duplicates.

- Screening:

- 955 screened based on title and abstract.

- 920 excluded based on titles and abstract (irrelevant, non-English, non-French.

- 35 full text qualitative articles assessed for eligibility.

- 28 full-text articles excluded (e.g., irrelevant, non-English, non-French, etc.).

- Inclusion:

- 6 studies included in COVID-19 qualitative synthesis.

- 1 study related to Social Determinants of Health.

- 5 studies related to Mental Health Inequalities

Data Extraction

Guided by Noyes & Lewin’s handbook of “Extracting Qualitative Evidence,” (2011) we created an extraction table to document key findings of the included studies. Since the original goal was to describe and map the literature, we chose the following fields for data extraction: 1) author(s), 2) year, 3) title, 4) aim, 5) research question, 6) study setting, 7) theoretical background of the study, 8) study design, 9) participant characteristics, 10) data collection methods, 11) data analysis approach, 12) key themes identified, 13) data extracts related to key themes, 14) author explanation of key themes, 15) author recommendations. As we immersed ourselves in the literature, however, and given the variety and diversity of findings, we added additional fields to the extraction table, aligning with our modified approach to using a framework synthesis. As such, we added the eleven determinants of health used in our quantitative analysis: 1) sex/gender, 2) age, 3) marital status, 4) immigration status, 5) Indigenous identity, 6) race/ethnicity, 7) educational attainment, 8) income, 9) employment status, 10) housing ownership status and 11) sense of community belonging.

Assessment of Study Quality

We conducted an assessment of study quality based on the framework by Tracey and Hinrichs who outlined the criteria for high quality qualitative research (Tracey & Hinrichs, 2017). While this article identified eight different criteria, the reviewers discussed and came to a consensus on using five of the eight criteria that were most relevant to the narrative synthesis. The five criteria for study assessment included assessment of worthy topic, rich rigor, credibility, significant contribution, and meaningful coherence.

Data visualization

We used the online application MIRO to create a mind map outlining relevant topics and details from study extractions. An iterative process was used to organize themes and findings of the literature, which evolved over the course of the review. As a first step in the synthesis, we created a mind map of study topics and sub-populations studied (see figures 3 and 4 below).

Figure 3. Mind Map of Topics Identified Literature Review

- Topics

- Suicidality

- Post Partum Depression

- Disordered eating

- Substance use

- Housing and Homelessness

- Under/unemployment

- Community participation, community belonging and social isolation

- Sexual Harassment

- Sexual healthcare experiences

- Experiences of migration

- Access/barriers to care

- Social determinants of mental wellness

- Gang affiliated, street level dealing and crime

- Bullying/Peer-based aggression

- Entrapment (abuser, trauma, system)

- Intimate Partner Violence (IPV)

Figure 4. Mind Map of Sub-populations Identified in Literature Review

- Sub-populations

- Street involved populations

- Street involved women (history of crack cocaine use)

- Women who use drugs at Overdose Prevention Sites (OPS)

- Persons who inject drugs (PWID)/Injection drug users (IDUs)

- Street involved youth (methamphetamine use)

- Sexual minority men who use substances

- Men

- Single Men

- Unemployed Men

- Heterosexual Men

- Immigrant and Refugee Men

- Men who have lived alone

- Women

- Individuals that have experiences postpartum depression (PPD)

- Females that have experienced PPD

- Immigrant/refugee women experiencing/have experienced PDD

- Lone mothers on social assistance

- Sexual Minority women

- Individuals that have experiences postpartum depression (PPD)

- Indigenous populations

- Pregnant-involved Aboriginal women

- Indigenous elders

- Métis adults in BC

- nêhiyawak (Plains Cree)

- Sexual Minority

- Sexual Minority Men (gay, bisexual, queer)

- LGBTQ+ youth

- LGBTQ+ adults

- Sexual Minority Women (gay, bisexual, queer)

- Transgender

- Transgender individuals

- Transgender youth

- Medical Students

- Individuals with severe mental illness (SMI)

- Older adults

- Racialized groups

- Muslim Women

- Racialized immigrant women

- South Asian youth

- Individuals who experience homelessness

- Male and female psychiatric survivors

- Front line workers, social service workers and service providers

- Street involved populations

Quantitative Literature Review

Objective

In order to guide the direction and scope of future analyses on mental health inequalities in Canada, there was a need to identify the state of contemporary evidence that explores social determinants of and inequalities in mental health outcomes in Canada. A rapid literature review was performed.

The review aimed to identify literature that summarizes inequalities in mental health (specifically, self-reported mental health, suicidality, mental health-related hospitalizations, and mood and depressive disorders) in Canada between two or more population sub-groups as defined by measures of social or economic status or identity (i.e. social determinants), and explores the economic and social conditions that give rise to such inequalities.

Methods

Search Strategy

Literature search was conducted in three phases. First, we searched for literature reviews, synthesis reports, and individual articles in PubMed from 2018 to 2022 (to cover the period following the publication of the last HIRI report in 2018). Additional literature was found by searching references of relevant articles identified. In the second phase, peer-reviewed literature that was published during the COVID-19 pandemic period (March 2020 to January 2022) was obtained from an on-going literature scan process conducted by the Public Health Agency of Canada (Equity Analysis and Policy Research Team). The scan process involved a continuous search of the following databases: MedRxiv, WHO COVID-19, PubMed, Scopus, BioRxiv, SSRN, Research Square, arXIV. These articles were all related to COVID-19 or SARS-CoV-2. In the last phase, grey English and French literature was identified in Google and Google Scholar through reviewing the first 5 pages of results outputted from our search strategy while using the google filtering system to filter for studies from after 2017 and in Canada. This search was performed between January 11, 2022 and January 20, 2022.

Search Terms

In the PubMed database, the following terms, described in the table below, were searched in the titles and abstracts of articles.

Table 1. Search themes and terms (searched 2022-01-11) in PubMed

| Theme | Search terms (English) | Search terms (French) |

|---|---|---|

| 1) Social Determinants | Social determinants, social determinants of health, health determinants, social environment, socioeconomic factors, socioeconomic status, socio economic status, social strata, social stratum, social status, material deprivation, social deprivation, area-level deprivation, disadvantage, disadvantaged vulnerable, social identit*, social position*, social cohesion, social capital, racism, race, racialized, race-based, cultural background, racial, ethnicity, minority group*, ethnocultural group*, enthocultural concentration, sex, gender, LGBTQ2, LGBT, LGBTQ, sexual orientation, sexual minority, gender-based, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, two-spirited, Indigenous, Aboriginal, Inuit, Métis, First Nations, indigenous people*, indigeneity, rural, urban, newcomer, immigrant*, immigrant status, foreign-born, refugee*, ableism, disabil*, age, income, poverty, income inequal*, insurance, social assistance, social welfare, education, educational attainment, high school, university, occupation, employment, job security, working conditions, healthcare access, material deprivation, social deprivation, housing, housing status, homeless*, houseless* | Déterminants sociaux, déterminants sociaux de la santé, déterminants de la santé, environnement social, facteurs socio-économiques, statut socio-économique, strate* sociale, statut social, privation matérielle, privation sociale, privation au niveau de la zone, désavantage, défavorisation, défavorisé vulnérable, identité sociale*, position sociale*, cohésion sociale, capital social, race, racisé, fondé sur la race, origine culturelle, racisme, raciale, ethnique, groupe minoritaire*, groupe ethnoculturel*, concentration enthoculturelle, sexe, genre, LGBTQ2, LGBT, LGBTQ, orientation sexuelle, minorité sexuelle, lesbienne, gay, bisexuel, transgenre, bi-spirituel, indigène, autochtone, Inuit, Métis, Premières Nations, peuple indigène*, indigénéité, rural, urbain, nouvel arrivant, immigrant*, statut d'immigrant, né à l'étranger, réfugié*, handicap, âge, revenu, pauvreté, inégalité de revenu*, assurance, assistance sociale, bien-être social, éducation, niveau d'éducation, collège, collég*, université, profession, emploi, sécurité de l'emploi, conditions de travail, accès aux soins de santé, défavorisation matérielle, défavorisation sociale, logement, statut du logement, sans abri*, sans logement* |

| 2) Health Inequalities | Inequalit*, inequit*, disparit*, unequal, equity, Health inequalit* , health inequit*, health disparit*, health status inequal*, health status inequit*, health status disaprit*, social inequit*, marginaliz* | Inégalité*, inégalité*, disparité*, équité, Inégalité de santé*, disparité de santé*, inégalité de l'état de santé*, inégalité en matière de santé, inéquité en matière de santé, inégalité de l'état de santé*, disparité de l'état de santé*, inégalité sociale*, marginalisation* |

| 3) Mental Health | Self-reported mental health, self-rated mental health, serlf perceived mental health, self-assessed mental health, self-harm, self-inflict*, suicide*, suicidality, suicidal, mental illness hospitalization*, mental health hospitalization*, mental health emergency department, mental health emergency visit*, mental illness emergency department, mental illness emergency visit*, affective disorder*, mental disorder*, anxiety, depress* | Santé mentale auto-déclarée, santé mentale auto-évaluée, santé mentale perçue, automutilation, auto-mutilation*, suicide*, suicidalité, suicidaire, hospitalisation pour maladie mentale*, service d'urgence pour maladie mentale, visite d'urgence pour maladie mentale*, trouble affectif*, trouble mental*, anxiété, dépression* |

| 4) Canada | Canad*, Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Newfoundland, Labrador, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Prince Edward Island, Quebec, Québec, Saskatchewan, Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Yukon | Canad*, Alberta, Colombie-Britannique, Manitoba, Nouveau-Brunswick, Terre-Neuve, Labrador, Nouvelle-Écosse, Ontario, Île-du-Prince-Édouard, Québec, Saskatchewan, Territoires du Nord-Ouest, Nunavut, Yukon |

| 5) Reviews | Synthesis *, review* | Synthèse*, revue* |

Notes

Search strategy “blocks”: (Social determinants OR health inequalities) AND (mental health) AND (Canada) AND (Reviews). All terms searched in Title & Abstract from Jan 2018-Jan 2022.

Retrieved results: N= 196

Total included: N= 8

Table 2. Grey literature search strategy and results (searched 2022-01-18) in Google*

| Search Engine | Search Terms | Pages Searched | Websites screened | Excluded (newspaper, irrelevant) | Included | Full-Review | Final |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

“Mental health”, “Inequalities” “Canada” |

5 |

50 |

41 |

9 |

9 |

2 |

|

Google Scholar |

“Mental health”, “Inequalities” “Canada” |

5 |

50 |

38 |

12 |

12 |

6 |

|

|

“Santé mentale” “Inégalités” “Canada” |

5 |

50 |

35 |

15 |

15 |

1 |

|

Google Scholar |

“Santé mentale” “Inégalités” “Canada” |

5 |

50 |

45 |

5 |

5 |

0 |

Notes

*All searches filtered for literature after January 1st, 2018 and by Canada using google search filtering system.

Eligibility criteria

To be included, the literature had to meet the following inclusion criteria: they were required to have been 1) published in or after 2018, 2) to quantitatively or qualitatively summarize inequalities in affective mental health (self-reported mental health, suicidality, mental health-related hospitalizations, mood and anxiety disorders) in Canada between two or more population sub-groups, as defined by measures of social or economic status or identity (i.e., social determinants). Conference abstracts, opinion pieces, editorials, news articles, were excluded. Further, literature was excluded if it focused on schizophrenia, medically assisted suicide, reproductive mental health, gambling, cannabis related mental illness, and eating disorders, or were studies on screening and treatment effectiveness, as these were out of scope for our focus. Papers were also excluded if the sample used was clinically unique and niche from the general population due to limitations of it being ungeneralizable.

Table 3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Literature Review

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

Data Extraction and Synthesis

For the literature obtained from the PubMed database, Rayyan was used to scan titles and abstracts of identified works to identify relevant articles. If the work met the criteria, a full text review was conducted to extract data into a summary table using Microsoft Excel. In regards to the literature obtained from the on-going COVID-19 scan, an excel file pooling all literature from the on-going scan was used. This file was filtered to find reviews and articles focusing on mental health as their primary or secondary outcome. Articles were then scanned based on their titles, objectives, and summary written by a PHAC colleague. If the work met the criteria, a full text review was conducted to extract data into a summary table using Microsoft Excel.

Grey literature was gathered from Google and Google scholar by scanning the title and full text of search results. Data of identified relevant articles was extracted into the Excel summary table.

References were stored and managed using Mendeley software.

The following items were extracted from each relevant work: Last name of all authors or authoring organization, article title, publication year, setting (provincial OR territorial or national jurisdiction of the study), population type and age group, data source(s) (including survey cycle years if relevant), outcome measure(s), exposure or disaggregation measure(s), inequality metric(s), adjustment variables for inequality estimation, key results (observed inequalities).

Selection

A total of 196 peer-reviewed studies were identified but 8 were included through PubMed (Phase 1 search). Two peer-reviewed studies were handpicked by carefully analyzing the references of the peer-reviewed studies identified in phase 1. Then, a combination of 118 peer-reviewed articles and grey literature reports were identified through the evergreen scan of COVID-19 related reports, of which 12 peer-reviewed articles and 2 grey literature reports were included (Phase 2 search). Lastly, 41 grey-literature reports and studies were identified through Google-based searches, with 10 passing for inclusion (Phase 3 search). This resulted in a total of 34 pieces of literature to be included in the review.

Measuring changes in mental health inequalities through time

Information about rate trends and changes in inequalities estimation, stratification by individual-level measures and by area-level measures (available in data tool only), data reportability rules, gaps and limitations.

Data Sources

This report draws on annual cycles of the Canadian Community Health Survey conducted between 2007 and 2022. The CCHS is nationally representative of the population age 12 and older in all provinces and territories, excluding those living on reserves, active-duty military, institutionalized persons, and persons residing in the Quebec health regions of Région du Nunavik and Région des Terres-Cries-de-la-Baie-James. Exclusions combined make up less than 3% of the Canadian Community Health Survey’s target population.

For findings pertaining to unmet need for mental health services, two secondary data sources were used as the outcome (indicator) was not collected consistently across CCHS cycles: CCHS Mental Health (2012), Mental Health and Healthcare Access Survey (2022). These specialized mental health household surveys are representative of individuals 15 and older living in the 10 provinces and follow a similar sampling design as the annual CCHS.

For symptoms of anxiety and depression disorders, data presented draw on two cycles of the Survey on COVID-19 and Mental Health (SCMH). Data was collected between September 11, 2020 and December 4, 2020 and then between February 1, 2021, and May 7, 2021. The SCMH is representative of the population age 18 and older in all provinces and territorial capitals, and follow a similar sampling design as the annual CCHS. The SCMH used screening tools to measure symptoms associated with major depressive disorder (Patient Health Questionnaire, PHQ-9) and generalized anxiety disorder (Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale GAD-7). Findings do not necessarily reflect a clinical diagnosis by health care providers, but rather the prevalence of mental health disorders symptoms and probable diagnoses at the population level. Because both PHQ-9 and GAD-7 are shorter screening tools, they are not comparable to those used previously in the CCHS Mental Health (2012). Of note, the PHQ-9 has been used in the 2015 to 2020 CCHS cycles.

For more information about each survey, please refer to Statistics Canada Surveys and statistical programs .

Outcomes (indicators)

- Anxiety disorder diagnosis: percent of people who reported that they have been diagnosed with an anxiety disorder such as a phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder or a panic disorder.

- Depression and anxiety symptoms: percent of people who may have a major depressive episode and generalized anxiety disorder in the past 12 months/lifetime. The assessment was conducted using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7). For both conditions, a score of 10 or more indicated moderate to severe symptoms.

- Excellent/very good self-rated mental health: percent of people who reported their mental health was excellent/very good.

- Flourishing mental health: percent of people with flourishing mental health vs. languishing or moderate mental health. Flourishing mental health was measured by the Mental Health Continuum—Short Form (MHC-SF) and refers to a combination of feeling good about and functioning well in life. Using the categorical scoring proposed by Keyes, responses indicating “almost every day” or “every day” to at least one of the three emotional well-being questions and six or more of the 11 positive functioning questions signify flourishing mental health.

- Help received because of problems with emotions, mental health or use of alcohol or drugs: percent of people who reported “yes” they had received help in the past 12 months, including information about these problems, treatments or available services, medication, counselling, therapy, or help for problems with personal relationships, other help.

- High life stress: percent of people who reported that most days in their life were quite or extremely stressful (vs. a bit or not very or not at all stressful).

- Mean life satisfaction: reported level of satisfaction with life as a whole right now on a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 means “very dissatisfied” and 10 means “very satisfied.” Trends for this indicator exclude 2007-2008 data as those CCHS waves used a different life satisfaction scale.

- Mood disorder diagnosis: percent of people who reported that they have been diagnosed by a health professional as having a mood disorder, such as depression, bipolar disorder, mania or dysthymia.

- Mood and/or anxiety disorder diagnosis: percent of people who reported that they have been diagnosed by a health professional as having a mood disorder (depression, bipolar disorder, mania or dysthymia) and/or anxiety disorder (phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder or a panic disorder).

- Poor/fair self-rated mental health: percent of people who reported their mental health was fair/poor.

- Suicidal ideation (thoughts): percent of people who reported that they have seriously contemplated suicide in the past 12 months/lifetime.

- Suicide attempt: percent of people who reported that they have seriously attempted suicide in the past 12 months/lifetime.

- Unmet need for mental health services: percent of people who reported having mental health service needs that were partially or not met.

Stratification used to Define Population/Social Groups

Stratification by individual-level measures

For annual cycles of the CCHS conducted between 2007 and 2022, data are disaggregated by the below stratifiers and by sex/gender (females, males). For all analysis, the reference group used for comparison among population groups was that which was presumed to be the most socially advantaged.

| Stratifiers | Categories and Description |

| Access to regular healthcare provider |

|

| Age group |

|

| Education (aged 20+) |

|

| Employment status (aged 18-75) |

|

| First Nations/Inuit/Métis identity |

|

| Household income quintiles1 |

|

| Household food security2 |

|

| Housing tenure |

|

| Immigration status |

|

| Living alone |

|

| Marital status |

|

| Occupational mismatch - Overqualified (aged 18-75)3 |

|

| Occupation (aged 18-75) |

|

| First official languages spoken |

|

| Race/Ethnicity identity4 |

|

| Race/Ethnicity by immigration status |

|

| Sense of community belonging |

|

| Sexual orientation (aged 15-59) |

|

| Urban/rural residence |

|

| Working multiple jobs (aged 18-75) |

|

| Work hours |

|

Q: Quintile

1 Income quintiles are based on self-reported household income adjusted for household size, community size, and province of residence.

2 Levels of household food insecurity are derived from responses to the Household Food Security Survey Module, which contains 18 questions that capture a household’s uncertain, insufficient or inadequate food access due to limited financial resources over the past 12 months.

3 Population aged 18-75 years with university education working in positions usually requiring high school education or less (National Occupational Classification skill levels C and D).

4 CCHS asks to which group(s) respondents identify: South Asian, Chinese, Black, Filipino, Latin American, Arab, White, Southeast Asian, West Asian, Korean, Japanese, and other (specify). In our categorization, only respondents who self-identified as belonging to only one population group were categorized in that group (i.e., anyone identifying as 2 or more groups were categorized as “mixed origins”). This differs from Statistics Canada’s use of the visible minority concept as defined by the Employment Equity Act. We also combined some population groups due to small sample sizes.

Joint stratification by individual-level measures (Intersecting categories)

Joint stratification is available to capture the intersection of identities or social positions based on two stratifiers (e.g., how race/ethnicity and employment simultaneously influence excellent/very good self-rated mental health). For example, a joint stratification measure capturing intersections between race (2 categories: Racialized, White) and employment status (2 categories: Not employed, Employed) could include the following four categories: Racialized not employed, Racialized employed, White not employed, White not employed. Intersecting categories in terms of different strata combinations are listed below for a subset of indicators.

| Outcomes (Indicators) | Intersecting categories | |

|---|---|---|

|

Health Determinants (Stratifier A with 2 categories) |

Population Groups (Stratifier B with 2 categories) |

|

|

|

|

Stratification by area-level measures

To better understand inequalities between geographical areas, area level measures 1 of socio-economic status were derived from survey data using Statistics Canada’s Canadian Index of Multiple Deprivation.

Data are disaggregated by the below measures and by sex/gender (females, males). Stratification measures include:

- Neighbourhood material resources index [Q1 least deprived (reference), Q2, Q3, Q4, Q5 most deprived]: Quintile levels indicate the relative area-level concentration of individuals who had access to and attained basic material needs (e.g., % of population unemployed and % of population without a high school degree).

- Neighbourhood immigration and visible minority index [Q1 least diverse (reference), Q2, Q3, Q4, Q5 most diverse]: Quintile levels capture the relative area-level concentration of individuals who were designated as a visible minority, recently immigrated to Canada or were born outside of Canada, or have no knowledge of either official language of Canada (English and French). This index was previously called ethno-cultural concentration.

Quintiles were constructed by ranking all DAs from the lowest indices (of neighbourhood material deprivation or diversity) per single-person equivalent to the highest, and by assigning DAs to 5 groups, such that each group contained approximately one-fifth of the total in-scope population. The least deprived or diverse DAs were categorized as Quintile 1. The most deprived or diverse DAs were categorized as Quintile 5.

Area-level measures are based on the 2016 Census Dissemination Areas (DAs), which are small relatively stable geographic units with average populations of 400-700 persons. For the development and dimensions of Canadian Index of Multiple Deprivation, please refer to Canadian Index of Multiple Deprivation User Guide .

CCHS waves conducted between 2007-2011 were linked to the 2006 index and CCHS waves conducted in 2012 and later were linked to the 2016 index. Of note, characteristics of the DAs may have changed between 2016 and reporting periods, and this represents a potential source of measurement error in these analyses.

Calculating inequalities and change over time

In order to have a large enough sample size for stratifying population groups, several years of CCHS data were combined to present estimates Footnote 5 for the following time intervals: 2007-2010, 2011-2013, 2014-2016, 2017-2019, 2020-2022 (also referenced as COVID-19 period). For life satisfaction, analysis excludes 2007-2008 data, which used a different scale. In the absence of repeated rounds of the CCHS Mental Health (2012) and the Mental Health and Healthcare Access Survey (2022), data collection time points were used to assess change over time. Further, data from the 2020 SCMH and 2021 SCMH were combined to assess the magnitude of inequalities by sociodemographic characteristics at one point in time.

Based on the Census 2016 age distribution, we estimated age-standardized means or proportions for each outcome, stratified by each population/social group and time interval. Each of these social stratifiers was further disaggregated by sex/gender (males and females). Estimates incorporated survey sampling weights, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using 500 bootstrap replication weights.

Differences and ratios were calculated from age-standardized means and proportions to examine contrasts between social stratifiers and/or time intervals. For each outcome-social stratifier combination, we present complete case analysis (i.e., sample size equals all respondents with valid responses for the outcome, social stratifier, age, and sex/gender). Changes in absolute and relative inequality compared baseline (2007-2010) to the latest (2020-22) time interval. The choice of inequality measures and change over time was informed by domestic and international approaches Footnote 6 Footnote 7 Footnote 8 to monitoring health inequality and further refined in discussions with the project’s steering committee.

Estimates were reported along with the corresponding 95% CIs. Statistical significance was assessed using 95% confidence intervals. The 95% CIs also illustrated the degree of variability associated with a given estimate. Wide confidence intervals indicated high variability in results and should therefore be interpreted with caution.

Analyses were performed using survey commands in R and Stata.

Data Reportability (data suppression)

Estimates were suppressed for privacy concerns or due to unstable results (also known as data quality issues). Suppression rules applied include:

- If there are fewer than 5 observations in the numerator estimates are suppressed.

- The reportability of numerators and age-standardized rates are based on their coefficient of variance (CV) using bootstrap weights:

- If CV < 15, the rate is reportable;

- If 15 ≤ CV ≤ 35, the estimate is reportable with caution, represented by the letter E;

- If CV > 35, the estimate is not reportable, represented by the letter F.

- The reportability of inequality measures are based on the reportability of the numerators, means and rates.

Limitations

Limitations should be considered when interpreting results and findings. This report and accompanying data tool draw solely on health survey data. Patterns of inequalities are not comprehensively measured across multiple data sources. For instance, inequalities in mortality and hospital admissions from mood disorders were not covered in this report and have yet to be fully explored and understood.

Several years of data were combined to yield larger sample sizes for analysis (i.e., 3- years and 4-year period estimates for the CCHS). Although they have been widely used in health inequalities monitoring, period estimates may hide inequality patterns, across groups and over time, compared to estimates based on a shorter time period (e.g., annual estimates).

Further, one should not infer causality because of repeated cross-sectional design with data collected. Findings do not reflect differences over time in the same individuals. Rather, they describe pooled estimates of independent sets of individuals surveyed at different times for the purposes of inequality monitoring (in other words, indicate if and by how much inequality changed for different population groups).

Another limitation is that population-level measurement of structural and social determinants of mental health was not available. As alluded to earlier, survey instruments do not collect data on experiences of racism and different forms of discrimination (e.g., discrimination due to race or gender, homophobia, xenophobia, etc.). Further, the conflation of race and ethnicity in all surveys masks the distinctions between these two social constructs hindering our ability to report on inequalities that reflect these differences. The collection of both race-based and ethnicity data separately is a key step toward improved inequality monitoring in Canada.

In the beginning with the 2015 reference period, the CCHS question used to collect information on sexual orientation updated terminology and classifications that define response categories. For instance, the bisexual category was expanded to include pansexual and a write-in response to specify other sexual orientations was added since 2019. The minimum age for responding to questions was also expanded (i.e., from 18 to 59 years of age to respondents aged 15 and older in 2015). The goal was to use conceptual definitions that continue to evolve over time and for which there is no clear consensus definition or statistical standard. Therefore, to maintain comparability between cycles, this report used the age range from 15 to 59 years of age and response categories from earlier waves. Respondents who reported sexual orientations other than the 3 predetermined categories (i.e., heterosexual, gay/lesbian, and bisexual categories) could not be incorporated in the analyses due to the small sample sizes. Finally, measurement of sexual orientation excludes questions about sexual behaviours (included only in 2015–2016) and sexual attraction (unavailable in data collection instruments) is a limitation of estimates presented in this report.

Surveys also exclude First Nations people living on reserves and remote areas that include Inuit Nunangat (i.e., Quebec region of Nunavik and Région des Terres-Cries-de-la-Baie-James). As a result, our estimates do not provide a complete representation of the changes in mental health inequalities among First Nations and Inuit in these settings. It should also be noted that the CCHS had reduced coverage of populations targets in the territories up until 2012. For instance, in Nunavut, the coverage was only 71% because the survey was administered to the residents of only the 10 largest communities. As of the 2013 reference year, coverage was expanded to represent 92% of the targeted population. Given that Indigenous Peoples make up the largest proportion of the population in the territories, this limitation affects the representativeness of Indigenous Peoples in the years before 2013, and, consequently, the inequalities reported. Additionally, it is important to note that Indigenous Peoples in this report include survey respondents who identify as First Nations, Inuit or Métis. This standard may not reflect identities or definitions established by each Nation or People and it does not capture other aspects of Indigenous identity such as multiple Indigenous responses.

It is important to state that the CCHS has undergone two major redesigns. The first occurred in 2015, where significant changes were made to the methodology, including to sampling frames, data collection approach, and questionnaire content. The second redesign in 2022 involved a thorough review and update of the survey content and a transition to an online electronic questionnaire, enabling direct self-reporting by selected respondents. Consequently, caution should be taken when comparing data from previous cycles to data released for the 2015 and 2021 and for data released 2022. While we used content that was consistent and deemed comparable over time, it is possible that trends observed may have been influenced by different methodologies used in the CCHS as opposed to a true population phenomenon (i.e., there are competing explanations that cannot be disentangled). However, we have performed secondary analysis to inspect yearly estimates in mental health outcomes and social determinants. No outlier values were found and annual trends pre- and post-2015 redesign were relatively stable. Results were also consistent with different groupings of years combining past cycles of the 2015 CCHS, showing results are robust to alternative combinations of CCHS cycles. Detailed methodology concerning survey design is available in the Canadian Community Health Survey - Annual Component (CCHS) .

Further, self-assessed measures of mental health used in this report are subject to response bias. Culture, nationality, age, and other social factors might influence respondents’ reports of mental health experiences, ranging from a misunderstanding of what a proper measurement is to willingness to respond to questions. For example, the question about sense of community belonging may be subject to different interpretations because the term “local community” is not defined. As a result, respondents might understand “local community” in different ways. If systematic, such a response bias could lead to either under- or overestimating inequalities reported.

Lastly, a consideration when interpreting the findings is that the COVID-19 pandemic had major impacts on the data collection operations for the 2020 CCHS, resulting in significantly lower response rates than other annual waves. Despite survey weight adjustment to minimize bias due to survey non-response, some caution should be taken when comparing estimates between 2020 and other CCHS wave.

Future assessment of trends in mental health and how inequalities changed over time is needed to address these data gaps and limitations.

References

- Footnote 1

-

Noyes J, Booth A, Moore G, Flemming K, Tunçalp Ö, Shakibazadeh E. Synthesising quantitative and qualitative evidence to inform guidelines on complex interventions: Clarifying the purposes, designs and outlining some methods. BMJ Glob Heal. 2019;4(Supplement1).

- Footnote 2

-

Jack SM. Utility of qualitative research findings in evidence-based public health practice. Public Health Nurs. 2006;23(3).

- Footnote 3

-

Mays N, Pope C, Popay J. Systematically reviewing qualitative and quantitative evidence to inform management and policy-making in the health field. Vol. 10, Journal of Health Services Research and Policy. 2005.

- Footnote 4

-

Keyes CLM. Promoting and protecting mental health as flourishing: A complementary strategy for improving national mental health. Am Psychol. 2007;62(2):95–108.

- Footnote 5

-

Thomas S, Wannell B. Combining cycles of the Canadian Community Health Survey. Health Rep. 2009;20(1).

- Footnote 6

-

Public Health Agency of Canada. Monitoring changes in health inequalities through time: A scan of international initiatives and a rapid review of scientific literature . 2022.

- Footnote 7

-

CIHI. Trends in Income-Related Health Inequalities in Canada. 2016.

- Footnote 8

-

World Health Organization. Handbook on health inequality monitoring: with a special focus on low-and middle-income countries. 2013.

- Date modified: