Inequalities in mental health, well-being and wellness in Canada

Trends in mental health inequalities in Canada. Highlights changes over time and drivers of mental health inequalities.

- Last updated: 2024-09-10

For a pdf copy of this report, please contact health.inequalities-inegalites.en.sante@phac-aspc.gc.ca

Download

the executive summary

(PDF format, 417 KB, 11 pages)

Published: 2024-09-10

On this page

1. Introduction

Mental health is an issue of increasing importance for people living in Canada, and it is becoming more widely discussed in civil society; it is also increasingly a public health priority Footnote 1 . The ability to respond to mental health issues, whether during health crises, climate change events, economic downturns, or other conditions, depends on a shared understanding of the contexts within which mental health inequalities can arise and how they have changed over time.

The focus of this report is to provide an overview of mental health inequalities by examining the structural and social determinants of health that contribute to mental health outcomes. The structural determinants of health encompass processes such as economic, and political mechanisms that give rise to disparities in between populations within society Footnote 2 . Social determinants of health are the nonmedical factors in our lives that affect our health—where we live; our income, education, job, and access to health care; and our social connections Footnote 2 . (Refer to Box 2.1 for more definitions of key terms).

Changes in mental health outcomes over time are assessed using measures of life satisfaction, perceived mental health, well-being, and mental illness. Also examined is whether mental health, as a whole and within specific populations, has improved or worsened. This report also aims to increase the understanding of how some root causes shape inequities in mental health outcomes.

The full set of results and data visualizations can be found on the accompanying online data tool tab at https://health-infobase.canada.ca/mental-health/inequalities/data-tool.html . This includes both positive mental health and mental illness outcomes.

1.1 Positionality Statement

This report was developed as part of the Pan-Canadian Health Inequalities Reporting Initiative (HIRI), a collaborative undertaking by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), the Pan-Canadian Public Health Network, Statistics Canada, the Canadian Institute for Health Information, and the First Nations Information Governance Centre (FNIGC) . The HIRI mandate is to strengthen measurement, monitoring, and reporting of health inequalities in Canada. The initiative supports surveillance and research, informs program and policy decision-making to reduce health inequities, and enables monitoring of progress in this area over time.

Initiated in response to the Rio Political Declaration on Social Determinants of Health Footnote 3 , this work is aligned with the Federal Anti-Racism Secretariat’s guiding values of justice, equity, human rights, diversity, inclusion, decolonization, integrity, anti-oppression, and reconciliation Footnote 4 and with the Federal 2SLGBTQI+ Action Plan to advance equality for Two-Spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, and other sexual and gender-diverse (2SLGBTQI+) people in Canada Footnote 5 . This work also responds to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s nineteenth Call to Action to monitor the health inequities between Indigenous Peoples and non-Indigenous Canadians. Established in 2012, the HIRI has historically been informed by focusing on epidemiological data and methods, while incorporating social science and social epidemiological insights Footnote 6 , Indigenous worldviews Footnote 7 Footnote 8 Footnote 9 Footnote 10 Footnote 11 , and the social determinants of health framework developed by the World Health Organization ( WHO) Footnote 12 . The HIRI continues to use the same model of the social determinants of health—one that is also utilized internationally—to monitor inequalities in health outcomes and determinants among population subgroups of people living in Canada at the national, provincial, and territorial level and inform policy for health equity.

The HIRI is driven by an understanding that health inequalities cannot be addressed by the health sector alone. Employment, education, housing, and multiple other sectors need to jointly address social, economic, and political factors (for example, policies at various levels of government) that influence health, as well as the systems and structures that shape how these factors are distributed . Systemic forces refer to those which are manifested in each of society’s major parts, including the economy, politics and religion while structural forces refer to specific structures, such as laws, policies, institutional practices Footnote 156 . Both systemic and structural forces, such as racism, colonialism, xenophobia, heterosexism, ableism, and discrimination, generate and reinforce societal hierarchies, distributions of power and resources, and opportunities that inform and influence the social and material conditions into which individuals are born, grow, live, work, play, and age Footnote 13 . Tackling health inequalities requires a multilevel approach that includes policy interventions at the highest or macro level, through upstream action that redistributes opportunities for health in ways that are just for all, and at the meso level, through policy interventions in schools, communities, health services, and other settings.

After continued engagement with partners across federal government departments, national Indigenous organizations, and experts outside of PHAC, the HIRI has sought to enhance integration of Indigenous worldviews as well as feminist, intersectional, and decolonizing approaches in the planning and development of its reporting practices Footnote 14 . The HIRI continues to strive to integrate interdisciplinary theories and methodologies when monitoring and measuring health inequalities in Canada. This report is enriched by qualitative evidence gleaned from studies that used various methodologies such as participant observation, structured interviews, and other forms of fieldwork.

1.2 Aims and Objectives

1.2.1 Why focus on mental health?

Problems related to poor mental health affect individuals and the people around them and has far-reaching economic and societal implications. As a leading cause of disability in Canada Footnote 15 , poor mental health leads to greater absenteeism in the workplace and reduced productivity Footnote 15 . The financial costs of poor mental health, including mental illnesses, are substantial, at approximately $51 billion each year in health care expenditures and lost productivity Footnote 15 . The burden of mental health, in terms of economic and societal costs, increases when levels of high self-rated mental health are lower in the population.

Families frequently experience increased stress and disruption in daily life as well as financial difficulties as a result of supporting family members with mental health–related problems. Mental illness can contribute to social isolation and withdrawal from social activities, which can lead to decreased community engagement and strained relationships Footnote 16 , and, in turn, contribute to a cycle of poor mental health. Further, the stigma associated with mental illness and poor mental health in general can lead to discrimination, social exclusion, and reduced quality of life.

Taken together, the societal and economic toll of mental health is substantial. A comprehensive understanding of inequalities in mental health outcomes and their determinants is essential to developing strategies and interventions to improve the mental health of people in Canada.

1.2.2 Why focus on mental health inequalities?

Health equity is embedded in the World Health Organization (WHO) Constitution and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights Footnote 17 . The former proclaims that “the highest standards of health should be within reach of all, without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition” while the latter states that “everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control”. Health equity is concerned with creating equal opportunities for health for each member of a society. Advancing health equity means working towards eliminating unfair and avoidable differences between socially advantaged and disadvantaged groups that have poorer health status and shorter lives, a role for many within and outside the health sector Footnote 18 . One way to do so is to focus on systems and structures of power affecting different populations through the distribution of material and social resources within societies, known as social determinants of health. The social determinants of health refer to the conditions which we are born into, where we grow up, where we live, how and in what ways we work, and even how we spend our free time. They encompass the broader societal, economic, and environmental influences that significantly impact individual and community health outcomes, extending far beyond healthcare access and directly shape our overall health, including mental health.

According to the WHO Footnote 2 , the social determinants of health (such as income, employment, and housing) and the broader factors that shape living and working conditions account for between 30% and 55% of health outcomes, a much greater effect than lifestyle choices and activities (e.g., exercise). Compared to the health care system, our education, justice, and social welfare–related socioeconomic systems and political contexts have been found to contribute significantly to health outcomes Footnote 2 Footnote 19 Footnote 20 :

As we conceptualize these deeper layers, the core social determinants of mental health can be understood as stemming directly from unequal distribution of opportunity. Although it may affect individual patients and may be considered in formulations and intervention planning based on the biopsychosocial model, this unequal distribution of opportunity is primarily a concern about society. As such, it is a social justice issue, rather than a clinical issue. Social justice means fair distribution of advantages and equal sharing of burdens while focusing on those most disadvantaged. Footnote 21

Monitoring health inequalities over time is important in order to support public health actors, such as health professionals, community leaders, and others with an interest in the drivers of mental health inequalities; and public sector actors, for example , politicians, public servants, community organizations, and nongovernmental organizations that assess whether policies and programs contribute to or mitigate inequalities. This requires an improved understanding, description, and response to health inequalities to address the fundamental determinants of health and promote social justice and health equity Footnote 14 .

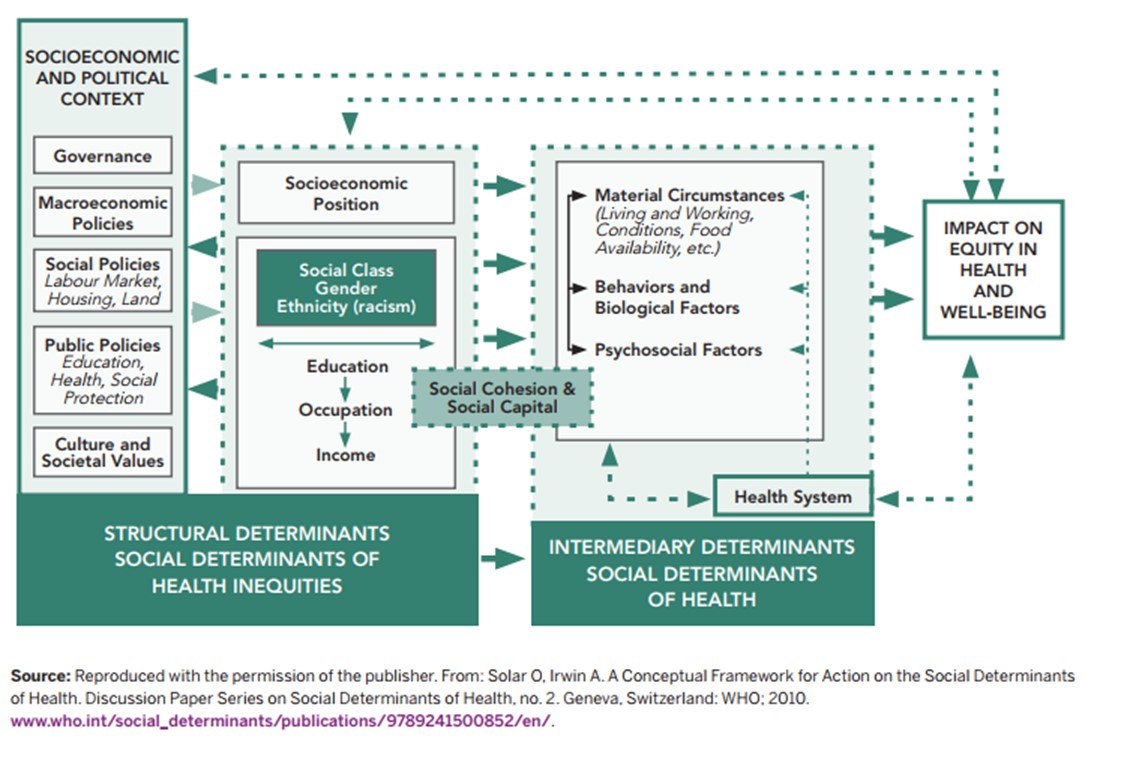

Various models have been developed to map and understand how determinants of health influence health outcomes. Informed by the WHO conceptual framework Footnote 12 , PHAC defines social determinants of health as the “social and economic factors … that relate to an individual’s place in society” Footnote 22 . The conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health developed by WHO (shown in Figure 1) has 2 levels of determinants: structural and intermediary .

The first level or structural-level determinants shape conditions for health through socioeconomic and political contexts. Social, economic, and other institutional policies, systems, and values shape health and well-being through the ways that power, resources, and opportunities are distributed within and between populations Footnote 13 Footnote 23 . Societal values—including prejudice and stigma towards populations or people with certain health conditions Footnote 24 —influence prevention opportunities and treatment options. In addition, broader economic and ideological systems, such as capitalism Footnote 25 , systemic racism, colonialism, sexism, heterosexism, and ableism Footnote 26 underlie policy approaches that influence social determinants of health, through decisions made regarding education, housing, the labour market, and societal protections. The structural determinants of health shape the socioeconomic position of individuals and of populations within society. This position is further affected by education, occupation, ethnicity, race, sex, gender expression, and sexual orientation, among others Footnote 13 Footnote 23 .

These structural determinants influence the second level or intermediary-level determinants of health. Intermediary determinants include factors related to the health system (e.g., health service availability, accessibility, uptake) and access to health-promoting social and material resources and opportunities, including the built environment, food environments, workplaces, and homes Footnote 13 Footnote 23 Footnote 26 .

In Canada, research has documented associations between various mental health outcomes and markers of social position such as age, sex, gender expression, sexual orientation, ethnicity, race, income, education, and employment status Footnote 13 Footnote 26 Footnote 27 Footnote 28 as well as intermediary factors such as food security, access to mental health care, quality of social ties, discrimination, stigma, and violence Footnote 24 Footnote 27 Footnote 29 Footnote 30 .

Figure 1. Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health (Solar & Irwin, 2010)

Figure 1: Text description

Using arrows, the framework indicates the interconnections and cyclical nature of measures concerning the social determinants of health. The framework consists of two main parts (parts A and B).

Part A, entitled “Structural Determinants, Social Determinants of Health Inequities”, comprises two main sub-sections. The first deals with the socioeconomic and political context, and includes governance, macroeconomic policies, social policies (labor market, housing and land), public policies (education, health, social protection) and societal culture and values. The second sub-section concerns socio-economic status, including social class, gender, ethnic origin (racism), education, employment and income. These two subsections are linked by bidirectional arrows.

Part B, entitled “Intermediate Determinants, Social Determinants of Health”, comprises three elements: material conditions, including living and working conditions, availability of food, etc.; behaviours and biological factors; psychosocial factors. The “health system” is also considered an element of Part B, but it appears in a separate box, linked by a bidirectional arrow to the main components of Part B.

One-way arrows link Part A to Part B, and a “Social cohesion and social capital” box also links these two sections.

Unidirectional arrows link Part B, in particular the “Health system” box, to a box on the far right of the diagram entitled “Impact on health equity and well-being”. Finally, two unidirectional arrows lead from the “Impact on health equity and well-being” box to the two main subsections of the “Structural Determinants, Social Determinants of Health Inequities” section (part A).

“Both public policies and social norms are structured such that they favour some individuals and groups over others, which sets the stage for the unequal distribution of opportunity, and thus the social determinants of mental health. Although clinical interventions clearly have a role in reducing risk for mental disorders, the greatest population-based impact for preventing many chronic physical health conditions and a number of mental disorders and substance use disorders would be achieved by optimizing public policies to make them more health promoting and by shifting social norms so that together we prioritize the health of all members of society.” Footnote 21

The pathways through which social determinants of health impact mental health and well-being can include events and conditions that are physiological and psychological stressors. Large-scale events, such as natural disasters, and individual-level circumstances, such as violence or material deprivation, can result in biophysical responses that negatively affect immune, metabolic, and endocrine systems Footnote 28 in addition to emotional and psychological well-being Footnote 28 . Individuals may turn to coping behaviours to mitigate these effects; these behaviours can be health promoting (e.g., meditation, exercise) or harmful (e.g., problematic substance use). However, the behaviours are always adopted in the context of the influence of social norms, values, life-stage factors, identity factors (e.g., gender, religious affiliation), availability of and access to supports, and so on, and they play a role in the intensity and duration of the impact of social determinants on one’s mental health.

Guided by the Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH), established by WHO, the HIRI primarily utilizes cross-sectional quantitative data to monitor health inequalities. We expand on previous reporting by examining both quantitative and qualitative evidence. Through a process of thematic analysis and synthesis of the findings of Canadian qualitative studies, and quantitative analyses of nationally representative survey data describing mental health inequality trends between 2007 and 2022, our aim was to develop a portrait of the key social and structural determinants of mental health and well-being in Canada.

This report pays special attention to upstream determinants including the socioeconomic, political, cultural, historical, and environmental factors that affect the mental health and well-being of people living in Canada. Although these upstream factors have often been considered removed from health outcomes, in fact they have profound impacts on health disparities and outcomes. Addressing upstream factors requires looking at systemic or societal issues, such as poverty, discrimination, access to education, and an equitable distribution of other resources. In integrating interdisciplinary perspectives and approaches, this report aims to broaden understanding of mental health and well-being.

In addition, this report has an accompanying online data tool that provides a comprehensive repository of mental health inequality trends to expand and complement the analyses presented in this report. This tool can be found at https://health-infobase.canada.ca/mental-health/inequalities/data-tool.html .

2. How is Mental Health Conceptualized in Canada ?

Mental health has been defined in many ways, with each definition influenced by social and cultural contexts Footnote 30 . Globally, there is no official consensus on a singular definition of mental health, and core concepts vary depending on different theories, models, and paradigms Footnote 31 .

In this section we summarize various common mental health constructs taken into account in this report.

2.1 Why Reflect on Definitions of Mental Health?

Several interdisciplinary health and social theories inform the HIRI and this report. One of these is intersectionality theory, a central principle of which is the importance of recognizing different forms or types of knowledge and ways of knowing Footnote 32 Footnote 33 . In the domain of public health, this can be applied by reflecting critically on the forms of knowledge that are considered valid and valuable in public health decision-making Footnote 14 .

A primary aim of this report is to explore how mental health is conceptualized in Canada, across epistemological perspectives and traditions. Broadly, this report understands mental health as an umbrella term that includes both positive and negative states of mental health.

Systematic exclusion of certain types and sources of evidence or voices can intentionally or unintentionally perpetuate the marginalization of certain communities and contribute to ongoing health and social inequalities. For example, if the people responsible for shaping policies and programs and the intended beneficiaries of these programs and policies are not involved in evidence synthesis and decision-making, the programs and policies may be designed in ways that do not meet the distinct needs of the communities they are meant to serve Footnote 32 . To counter this tendency, best practices in public health research and surveillance consider multiple ways of knowing and types of knowledge when defining key terms, issues, and concepts Footnote 14 . In this report, exploring how various sources, communities, or systems of knowledge production define or understand mental health can provide depth and nuance to mental health promotion initiatives.

Box 2.1. Key Terms and Their Definitions

|

Terms |

Definitions |

|

Health Inequalities |

Refer to differences in health status or in the distribution of health determinants between different population groups. These differences can be due to biological factors, individual choices, or chance. Nevertheless, public health evidence suggests that many differences can be attributed to the unequal distribution of the social and economic factors that influence health (e.g., income, education, employment, social supports) and exposure to societal conditions and environments largely beyond the control of the individuals concerned. |

|

Health Inequity |

Health inequity refers to differences in health associated with structural and social disadvantage that are systemic, modifiable, avoidable and unfair. Health inequities are rooted in social, economic and environmental conditions and power imbalances, putting groups who already experience disadvantage at further risk of poor health outcomes Footnote 34 . |

|

Health Equity |

Health equity means that all people (individuals, groups and communities) have fair access to, and can act on, opportunities to reach their full health potential and are not disadvantaged by social, economic and environmental conditions, including socially constructed factors such as race, gender, sexuality, religion and social status. Achieving health equity requires acknowledging that some people have unequal starting places, and different strategies and resources are needed to correct the imbalance and make health possible. Health equity is achieved when disparities in health status between groups due to social and structural factors are reduced or eliminated Footnote 34 . |

|

Social Determinants of Health |

The social determinants of health are the interrelated social, political and economic circumstances in which people are born, grow up, live, work and age. The social determinants of health (see below) do not operate as a list or in isolation. It is how these determinants intersect that causes conditions of daily living to shift and change over time and across the life span, impacting the health of individuals, groups and communities in different ways Footnote 34 . |

|

Structural Determinants of Health |

Structural determinants of health are processes that create inequities in money, power and resources. They include political, cultural, economic and social structures; natural environment, land and climate change; and history and legacy, ongoing colonialism and systemic racism. Structural determinants, also known as structural drivers, shape the conditions of daily life (social determinants of health) including education, work, aging, income, social protections, housing, environment and health systems Footnote 34 . |

|

Downstream (Micro) approaches |

Downstream interventions and strategies seek to address immediate needs and mitigate the negative impacts of disadvantage on health at an individual or community level through the availability of health and social services. These changes generally occur at the service or access-to-service level. Downstream strategies are about changing the effects of the causes Footnote 34 . |

|

Midstream (Meso) Approaches |

Midstream interventions and strategies reduce exposure to risk by improving material conditions or by promoting healthy behaviours. These changes generally occur where individuals who live with inequities are directed or referred to resources that support health at the regional, local, community or organizational level. Midstream approaches are about changing the root causes of health inequities Footnote 34 . |

|

Upstream (Macro) Approaches |

Upstream interventions and strategies dismantle and change the fundamental social and economic systems (structural determinants of health) that distribute the root causes of health inequities including wealth, power and opportunities. These changes generally happen at the provincial, territorial, national and international levels. They are about changing the cause of the causes of health and health inequities Footnote 34 . |

|

Intersectionality |

Intersectionality considers how systems of oppression (e.g., racism, classism, sexism, homophobia) interact to influence relative advantage and disadvantage at individual and structural levels. An intersectional orientation recognizes that the experience of multiple forms of discrimination and disadvantage has a cumulative negative effect that is greater than the sum of the parts. The intersectional nature of oppression and privilege means that people may have privilege in one or more forms even if they experience oppression in other domains Footnote 34 . |

|

Mental Health |

Refers to an umbrella term that encompasses an individual’s state of well-being (emotional, psychological, social), measured by levels of positive mental health (i.e., self-rated mental health, happiness, life satisfaction, psychological and social well-being) and/or experiences of mental health problems or mental illness (i.e., anxiety disorders, mood disorders, substance use disorders or others). |

|

Mental Illness (also known as Mental Disorders) |

Refers to a wide range of conditions that affect a person's thinking, emotions, behaviour, or mood. These conditions can vary in severity, duration, and impact on daily life. Mental illnesses can encompass various disorders such as depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and many others. |

|

Poor Mental Health or Problems related to Mental Health |

Refers to the presence of a negative state of mental health and can be used as general terms for mental distress, and/or mental disorders, and/or mental illness, and/or substance use disorders, and/or suicidality. Importantly, an individual can have poor mental health or problems related to mental health without necessarily having a mental illness. |

|

Positive Mental Health |

Refers to the presence of a state of positive mental health. The PHAC definition of positive mental health is “The capacity of each and all of us to feel, think, act in ways that enhance our ability to enjoy life and deal with the challenges we face. It is a positive sense of emotional and spiritual well-being that respects the importance of culture, equity, social justice, interconnections and personal dignity” Footnote 35 . |

|

Two-Spirit

|

The term “two-spirit” is used by some Indigenous People to refer to persons who identify as having both a masculine and a feminine spirit. The term describes a person’s sexual, gender and/or spiritual identity. Persons who identify as two-spirit may be attracted to persons of the same sex and/or may identify as gender diverse, and include people who in Western culture may be described as gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender, among others. The term “two-spirit” was introduced by Elder Myra Laramee during the Third Annual Inter-tribal Native American, First Nations, Gay and Lesbian American Conference, held in Winnipeg in 1990. |

|

Social Gradient in Health |

Refers to the consistent, incremental differences in health outcomes or status that correspond to variations in socioeconomic status or other social determinants. These gradients illustrate how health tends to improve as socioeconomic status rises, showcasing a stepwise pattern where individuals with higher social or economic positions generally experience better health compared to those in lower positions. |

|

Cross-cultural Validity |

Refers to the extent to which a concept, assessment, or measurement tool is meaningful, relevant, and accurately measures what it intends to across different cultures or cultural groups. It ensures that the tool or assessment is fair, reliable, and doesn't disproportionately favour or disadvantage any particular cultural group when used in diverse cultural contexts. |

|

Health Promotion |

Health promotion is the process of enabling people to increase control over, and to improve, their health. It moves beyond a focus on individual behaviour towards a wide range of social and environmental interventions. As a core function of public health, health promotion supports governments, communities and individuals to cope with and address health challenges. This is accomplished by building healthy public policies, creating supportive environments, and strengthening community action and personal skills Footnote 36 . |

2.1 Biomedical Definitions of Mental Health

The biomedical model of mental disorders presumes that there are biological causes for abnormalities in the brain that result in mental illness. Contextual factors such as social interactions, resources, systems, and determinants are not considered Footnote 37 Footnote 38 , and biomedical conceptualizations of mental illness and health typically centre on mental distress, illnesses, and disorders or conditions and tend to focus on their etiologies, diagnoses, and remediation with psychotherapeutic treatments.

From a clinical diagnostic and treatment perspective, mental illnesses (or disorders) refer to emotions, mood, difficulties in thinking, and/or behaviours that impede a person’s day-to-day functioning Footnote 39 . Mental illnesses are defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) Footnote 40 Footnote 41 . The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders describes more than 150 clinical mental diagnoses, such as major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder Footnote 42 and includes diagnostic criteria for conditions such as schizophrenia, bipolar and related disorders, trauma- and stressor-related disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), substance-related disorders such as alcohol use disorder, and eating disorders.

Biomedical definitions of mental health and illness tend to dominate among epidemiologists, policy analysts, researchers, and health management officials Footnote 43 , who focus on individual-level attributes and behaviours and prioritize individual-level measures Footnote 38 .

2.2 Mental Health Models

Some scholars have proposed that mental health exists on a continuum from poor to good, on which a person can move between effective functioning to severe and persistent functional impairment Footnote 44 . Shifts along this mental health continuum can occur in response to biological, psychological, social, and economic factors, as well as specific life stressors. Mental health is thought of as the absence of mental illness Footnote 45 Footnote 46 . This polar relationship between mental health and mental illness has been the basis of psychological and psychiatric understanding and assumptions Footnote 47 .

In contrast, the dual continua model views mental health and mental illness as interrelated but distinct phenomena, with positive and negative effects, that operate independently of each other Footnote 47 . A person can have good mental health even if they have a mental illness (or disorder). They can experience elements of both mental illness and mental health, physically or emotionally, at different times or concurrently.

In 2021, 1 in 3 people aged 15 years and older had experienced a mental illness or substance use disorder during their lifetime Footnote 48 . Further, 9.6% of the population aged 12 years and older reported having a diagnosed mood disorder Footnote 49 . However, individuals with a diagnosed mood and/or anxiety disorder or substance use disorder can still self-rate their mental health or life satisfaction as high Footnote 50 .

2.3 Positive Mental Health

PHAC defines positive mental health as “the capacity of each and all of us to feel, think, act in ways that enhance our ability to enjoy life and deal with the challenges we face. It is a positive sense of emotional and spiritual well-being that respects the importance of culture, equity, social justice, interconnections and personal dignity” Footnote 51 . As such, positive mental health is considered necessary to flourish Footnote 44 . It is also an integral component of the WHO definition of health as a “state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” Footnote 17 . Positive mental health also has proven effects on biological functioning, cardiovascular risk, and improved immunity Footnote 43 .

The components of positive mental health are multifaceted and include functioning (e.g., motivations) and positive affect (e.g., happiness), strengths, self-actualization, personal capacities, and existentialist approaches with eudemonic (e.g., positive experiences) and hedonic focuses (e.g., meaning in life) Footnote 43 .

In 2016, in consultation with the Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC), PHAC developed a conceptual framework to strengthen surveillance of positive mental health and its determinants Footnote 52 . The Positive Mental Health Surveillance Indicator Framework (PMHSIF) includes 5 outcome indicators and 25 determinant indicators spanning the 4 contextual domains of individual, family, community, and society. Positive mental health outcomes include self-rated mental health, life satisfaction, happiness, psychological well-being, and social well-being.

Interventions that support the mental health of populations should focus on promoting positive mental health by addressing the social and structural determinants to complement illness prevention, treatment, and support. The Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA) develops strategies to ensure equitable mental health care across the life course and within communities, focusing on mental health promotion, prevention, and early intervention Footnote 327 .

In 2021, around 60% of adults and youth aged 12 to 17 years reported very good or excellent mental health and 73% reported being usually “happy and interested in life” Footnote 35 . On average, adults and youth reported being relatively satisfied with their lives, with about one-third of adults and about one-half of youth reporting being “very satisfied” Footnote 35 .

Risk and protective factors, from the individual to the societal level, contribute to positive mental health. Individual determinants, for example, physical activit y, substance use (and, for youth, substance use by family members), resilience, and coping, can influence an individual’s positive mental health. Similarly, family determinants such as family relationships, parenting style (for youth), household composition, and household income can promote positive mental health. Community determinants include social support and networks, school and work environment, and neighbourhood environment. Mental health determinants a t the societal level include social justice, and discrimination and stigma. As such, positive mental health measures are most often subjective; although theoretical in nature, the measures have been empirically validated Footnote 43 .

2.4 Expanding the Definition of Mental Health

How mental health is understood and defined is both historically and culturally contingent. Considering Canada’s Indigenous population and its distinct ways of knowing and being , its historical and current immigration policies, and its culturally and socioeconomically diverse populations, conceptualizations, definitions, and experiences of mental health vary widely. However, existing policies, programs, and initiatives intended to address mental health rarely consider this diversity. Overall, existing initiatives and treatments mostly reflect dominant biomedical science and evidence-based medical practice. These mental health narratives are primarily derived from clinical and psychological research focused on middle-class, educated, younger Western populations Footnote 53 . Scholars have pointed out how the nature and production of evidence-based medicine is influenced by and reproduces systems of power and privilege, such as patriarchy and sexism, racism, colonialism, heterosexism, ableism, and classism and does not reflect the cultural diversity of countries like Canada Footnote 53 .

To address this limitation, it is necessary to acknowledge Canada’s heterogeneous population and consider systems of power, the broader social context, and intersecting determinants of mental health shaped by people’s respective needs and experiences to both understand how social and structural factors shape mental health and how to achieve equity Footnote 54 .

Indigenous perspectives on mental wellness acknowledge these and other factors to provide a more inclusive and holistic conceptual framework. “Wellness” in many Indigenous communities and cultures across Canada is understood to encompass mental, physical, spiritual, and emotional balance. Thus, wellness focuses on strengths rather than deficits, and highlights the role of social and cultural environments. This contrasts with mainstream western understandings of health, which as discussed in previous sections, largely focus on biological causes for abnormalities that cause illness. For this reason, in the context of discussing Indigenous perspectives, the discussion is framed around “mental wellness” rather than “mental health.”

Indigenous Peoples possess distinct and diverse worldviews that often embrace holism, relationality, circularity, and interconnection Footnote 8 Footnote 55 Footnote 56 Footnote 57 . Although they represent distinct cultural groups, a common perspective shared by many First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples is that health and wellness involve a balance of physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual aspects of life Footnote 58 Footnote 59 . In the following sections, we have taken a distinctions-based approach to exploring different understandings of mental wellness. Informed by a number of discussions with national Indigenous organizations, the sections reflect complementary but distinct ways of conceptualizing mental wellness.

2.4.1 First Nations

The First Nations Mental Wellness Continuum Framework Footnote 11 provides a comprehensive definition of mental wellness as a balance of the “mental, physical, spiritual, and emotional” Footnote 11 . The 4 dimensions are interconnecting and necessary for mental wellness at the individual, family, and community level. This balance is enhanced when individuals have purpose, hope, a sense of belonging, and a sense of meaning, all of which are key wellness outcomes.

From this perspective, mental wellness is supported by a number of layers and interconnected elements, with culture providing the foundation. Although different First Nations express and experience culture in different ways, there are some shared core beliefs and concepts: the Spirit (an inclusive concept of body–mind–heart–spirit ); the Circle (the patterns of life); Harmony and Balance; All My Relations (interconnectedness with people and nature); Kindness/Caring/Respect; Earth Connection; Path of Life Continuum; and Language. Culture, therefore, “is the expression, the life-ways, and the spiritual, psychological, social, material practice of this Indigenous worldview” Footnote 60 . First Nations’ culture and languages reflect a unique worldview that informs individual identities and their relationship with all aspects of creation. In this manner, culture guides First Nations’ unique ways of seeing, relating, being, and thinking. The knowledge contained within culture provides the foundation for individual and collective wellness and provides guidance across the life course.

2.4.2 Inuit

The Inuit-Specific Mental Wellness Framework defines mental wellness as “self-esteem and personal dignity flowing from the presence of a harmonious physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual wellness and cultural identity” Footnote 7 . From this perspective, mental wellness is not a singular concept; it encompasses mental health and mental illness, and aims to prevent violence, suicide, and harmful substance use Footnote 7 . The National Inuit Suicide Prevention Strategy expands upon this understanding of mental wellness by also recognizing the role played by resilience as “a resource that grows through an accumulation of protective factors, sometimes called health assets, which contribute to positive mental wellness, increased ability to deal with stress or adversity, and resilience-building behaviours” Footnote 61 .

Building protective factors that contribute to developing abilities, skills, and social supports that offer people the capacity to cope with stress and spring back from crises and trauma is an important component of the wellness concept. The National Inuit Suicide Prevention Strategy outlines some of these protective factors: coping with acute stress; family strength and support; optimal nurturing development; cultural continuity; social equity, and access to Inuit-specific mental health and wellness services and supports. Social equity is achieved by addressing the social determinants of Inuit health, namely quality early childhood development, culture and language, livelihoods, income distribution, housing, safety and security, education, food security, availability of health services, mental wellness, and the environment Footnote 61 .

For Inuit, the land carries great importance. Close connection with the land, nature, and harvesting activities is thought to promote overall health as well as mental wellness Footnote 62 . Eating country foods and spending time on the land helps establish and maintain a strong cultural identity, which is also considered a key protective factor for mental wellness Footnote 61 . Cultural continuity, which is another key protective factor in the Inuit wellness concept, can be supported via sustainable approaches to connecting Inuit with the land, culture, and language.

2.4.3 Métis

While the Métis National Council does not currently have a framework focused specifically on mental wellness, Métis communities, institutions, and Knowledge Holders continue to share their mental wellness knowledge throughout the Métis Homeland, including through reports and academic writing. For Métis people, health and wellness encompass not only physical health, but also a “state of balance and interconnected relationships between physical, mental, emotional, social, financial/economic, spiritual, environmental, and cultural well-being” Footnote 63 . Understandings of health and wellness are closely tied to connection with family and the wellness of others within kinship networks Footnote 56 . This worldview encompasses a connection to all things, including the land itself, all life on earth, other people, and a sense of identity and belonging Footnote 64 Footnote 65 . Traditional Knowledge, language, and cultural identity are foundational to health and mental wellness Footnote 9 . Engagement in cultural practices is seen as an important tool for promoting mental wellness, fostering cultural pride, self-esteem, and a sense of belonging Footnote 66 .

2.5 Differences and Similarities Across Definitions

In summary, there is no single definition of mental health. Definitions often differ based on whether mental health is being conceptualized as a state (e.g., mental illness), a dimension of health (e.g., mental health vs. physical health), by domain or discipline (e.g., psychiatry or public health), or even a social movement (e.g., mental hygiene). Conceptualizations have since been broadened to consider mental health as a domain of overall health and well-being, catalyzing more holistic, upstream, strengths-focused, and positive approaches. The WHO statement that “there is no health without mental health” Footnote 1 reflects this milestone.

3. Methodologies

This report used a range of methods to develop understanding of the structural determinants of mental health and drivers of mental health inequalities to address the overarching objectives of monitoring health inequalities . These are described in detail in the Technical Notes ( https://health-infobase.canada.ca/mental-health/inequalities/technical-notes.html ). In this section we describe the guiding framework of this project, intersectionality theory, which informed the decision to incorporate both qualitative and quantitative evidence in this report, and the literature reviews of both qualitative and quantitative evidence on the social determinants of mental health in Canada and trend analysis that summarizes patterns in national health survey data across time.

3.1 Intersectionality Theory as the Guiding Framework

Intersectionality theory and practice provided the guiding framework for this project. Emerging from early race, class, and gender analytical frameworks, intersectional approaches continued to develop in the crucible of the civil rights movement and Black feminist scholarship Footnote 67 Footnote 68 Footnote 69 Footnote 70 . Responding to the interlocking systems of anti-Black racism, sexism, heterosexism, and class oppression, intersectionality has been defined as a theory, a broad-based knowledge project, a research paradigm, an analytic framework, and a critical praxis. Intersectionality focuses on social inequality (e.g., oppression, discrimination, marginalization, and stigma) by paying attention to intersecting systems of power and privilege (e.g., racism, sexism, heterosexism, colonialism) Footnote 67 Footnote 71 . It references the critical insight that social positions such as race, ethnicity, class, sex, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, nationhood, ability, and age cannot be conceptualized as—nor operate as—unitary, mutually exclusive entities, but as relational and reciprocal social formations that cannot be separated Footnote 72 . Intersectionality emphasizes a need to consider and examine the ways in which interconnected systems and structures of power and oppression operate across time, place, and societal levels, contributing to unequal material realities and complex social inequalities Footnote 14 Footnote 32 Footnote 73 .

For this report, we bridged conceptual and methodological tools to better understand mental health inequalities in Canada, with the goal of examining these inequalities from new angles, specifically paying attention to systems of power. In particular, we focused on the core tenets of intersectionality theory, including: 1) an emphasis on the importance of equity (i.e., fairness) and social justice (i.e., the need for transformational change or action to challenge and address social inequalities) Footnote 74 ; 2) an understanding that social identities and hierarchies are constructed by systems of power; 3) critical reflection on what types of knowledge or evidence are considered valid and who participates in producing the knowledge used in decision-making; and 4) recognition that knowledge production, sociopolitical contexts, health determinants, and outcomes can vary over time Footnote 32 .

Communities living in vulnerable circumstances or experiencing disadvantages are often excluded from processes of knowledge production. Consequently, intersectional knowledge projects try to include diverse and appropriately represented voices, worldviews, and forms of knowledge (e.g., experiential, traditional, scientific) in decision-making processes in order to disrupt the reproduction of socially dominant modes of knowledge production hierarchies. Intersectionality explores various theories of knowledge to consider how concepts are understood and defined; it discusses how determinants of health (along axes such as race/ethnicity, sex/gender, class, sexual orientation) intersect or overlap with one another to shape health outcomes and the inequalities therein, over time and across contexts; it engages with concepts of power; and, overall, it provides evidence to help address structural determinants of health and reduce health inequalities.

Accordingly, this report incorporates both qualitative and quantitative evidence, exploring the tenets of intersectionality of seeking out, honouring, and bringing into conversation different forms of knowledge, engaging with a myriad of experts and partners throughout the research design process, and developing the narrative in conjunction with a steering committee comprising community-based, academic, and public policy actors (membership is shown in the acknowledgements section), who provided direction and feedback throughout the process.

Still, there is room for improvement. For example, directly engaging with and co-producing research with Traditional Knowledge Keepers, communities, and/or repositories would go beyond the conventional sources of peer-reviewed publications and academic voices that make up the majority of the evidence presented in this report.

3.2 The Role of Qualitative Research in Understanding Mental Health Inequities

Qualitative research methodologies contribute to knowledge and discourses that are not standardized and singular, providing rich descriptions of multidimensional experiences Footnote 75 Footnote 76 . In this report, qualitative studies have been synthesized to provide a larger context for differences in population based surveys in order to gain greater insight into the nature of mental health inequalities. Our use of qualitative evidence was purposeful and critical to examine the types of ideas underpinning how mental health was described and understood in different settings with multiple populations. Part of this exercise was to examine the theoretical perspectives that were the basis of the studies to see how authors framed the multiple dimensions that contribute to mental health. By applying an analysis that was guided by an intersectional approach, we paid special attention to the nuance and complexity of both social locations, contexts and of power relations that impact mental health (for example, negative experiences of certain populations in accessing care). Further, the adoption of a narrative synthesis of qualitative themes to guide the structure of the report adheres to the interpretive nature of qualitative methodologies, and thus reorients the report to enable examining structural and system-level contributions to mental health inequalities in Canada.

3.2.1 Qualitative Research Methods

For the qualitative component of the report, we conducted a rapid review Footnote 77 of qualitative studies of the social determinants of mental health and mental health inequalities from a Canadian public health perspective. The studies were published in a 10-year period (2012–2022). Searches spanned a spectrum of mental health terms (from positive to negative). However, it is important to recognize that the focus of health inequalities research has historically been deficit-based and qualitative results may reflect this perspective. The rapid review included peer-reviewed research that employed a variety of qualitative methodologies and focused on participants’ lived experiences of mental health to understand the complex contexts of mental health inequalities. A Health Canada librarian helped devise the search strategy and compile materials. Strict inclusion criteria were utilized, concordant with the research team’s capacity, to limit the review.

We adopted a staged and iterative literature search process to familiarize ourselves with the main topics of study, subpopulations, and the theoretical perspectives in research on inequalities in mental health. Since the focus was on peer-reviewed research published in academic journals, a publication bias might exist within the evidence synthesis. However, this initial review was supplemented with additional literature searches and other forms of knowledge were included, where necessary. Sources consulted for the sections focused on First Nations, Inuit, and Métis were identified through discussions with our Indigenous partners or using targeted searches for the topic of interest.

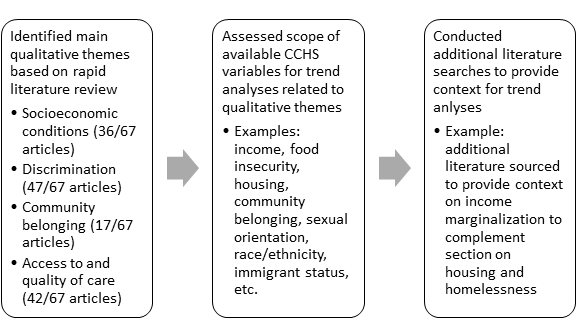

We followed a process of narrative synthesis to derive key themes in the body of evidence reviewed Footnote 76 . The goal of this process was to generate new insights by amalgamating study findings. Using an inductive approach, we extracted and synthesized the findings from 67 Canadian studies (out of a total of 588 initially identified). Key themes derived from the qualitative synthesis were: socioeconomic conditions; racism, xenophobia, homophobia, and other types of discrimination; social and cultural connection, support networks, and community belonging; and access, quality, and use of health care services. We conducted a supplementary search as a validation exercise to ensure that these 4 themes were consistent with systematic reviews of social determinants of mental health beyond the 10-year period initially searched. We found that the 4 identified qualitative themes were well represented and validated by the supplemental search Footnote 78 Footnote 79 Footnote 80 Footnote 81 .

Using these 4 themes, we used an iterative process to bring together qualitative and quantitative methodological approaches through principles of intersectionality and social epidemiology to better understand and describe mental health inequalities in Canada. For a visual representation of how we used the qualitative literature to drive the thematic analysis and selection of quantitative trends refer to Figure 2.

Figure 2: A visual representation of the thematic analysis and selection of quantitative trends

Figure 2: Text description

- Box 1 (Left): Identified main qualitative themes based on rapid literature

review

- This box lists the main qualitative themes that were identified from a rapid review of

67 articles. Each theme is accompanied by the number of articles in which it was

discussed:

- Socioeconomic conditions (37/67 articles)

- Discrimination (47/67 articles)

- Community belonging (17/67 articles)

- Access to and quality of care (42/67 articles)

- This box lists the main qualitative themes that were identified from a rapid review of

67 articles. Each theme is accompanied by the number of articles in which it was

discussed:

- Box 2 (Middle): Assessed scope of available CCHS variables for trend analyses

related to qualitative themes

- This box outlines the process of assessing the available variables in the Canadian

Community Health Survey (CCHS) that can be used for trend analyses aligned with the

qualitative themes identified in Box 1. Examples of these variables include:

- Income

- Food insecurity

- Housing

- Community belonging

- Sexual orientation

- Race/ethnicity

- Immigrant status, etc.

- This box outlines the process of assessing the available variables in the Canadian

Community Health Survey (CCHS) that can be used for trend analyses aligned with the

qualitative themes identified in Box 1. Examples of these variables include:

- Box 3 (Right): Conducted additional literature searches to provide context for

trend analyses

- This box describes the final step in the process, which involved conducting additional literature searches to enrich the context for the trend analyses. An example provided is the sourcing of literature on income marginalization to complement analyses focused on housing and homelessness.

3.3 Quantitative Research Component: Outcomes and Surveys

A trend analysis to assess mental health inequality over time used cross-sectional data from the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) (details in Technical Notes at https://health-infobase.canada.ca/mental-health/inequalities/technical-notes.html ) . Unless otherwise indicated, trends are presented for the following time intervals: 2007 to 2010, 2011 to 2013, 2014 to 2016, 2017 to 2019, and 2020 to 2022 (the COVID-19 period). This is to ensure sufficiently large sample sizes when analysing data for subpopulations. In 2015, Statistics Canada revised the CCHS methodology, including the sampling frames, data collection approach, and questionnaire content. However, examination of yearly trends in mental health outcomes and social determinants did not reveal any major anomalies around this time.

We chose to use the CCHS rather than any other national survey because it includes several mental health outcomes and social determinants, has a large sample size, and questionnaire content has been largely consistent across annual cycles. However, people living on reserves and in other Indigenous settlements in the provinces and those living in the Quebec health regions of Nunavik and Terres-Cries-de-la-Baie James are not covered by the CCHS, limiting findings on First Nations living on reserves and Inuit in northern communities of Quebec that are part of Inuit Nunangat. Moreover, the survey asks respondents to self-identify as First Nations, Inuit, or Métis, which may not always conform to the criteria set out by each Nation or People. With financial support from PHAC, the First Nations Information Governance Centre (FNIGC) is producing a report that focuses on the mental wellness of First Nations Peoples living on reserve and in northern communities. This report will use data from the Regional Health Survey, the first and only national health survey of First Nations. The FNIGC report, which is anticipated to be released in 2025, will complement and expand on some of the findings in this current report.

The quantitative analyses in this report focus on 2 positive mental health outcomes: mean life satisfaction and high self-rated mental health Footnote 35 . These measures were selected using qualitative assessments that took into account indicators previously used by the HIRI, coverage across population groups that are important to health equity, and a balance between Western and distinctions-based Indigenous understandings of mental wellness. Outcomes were prioritized because of the increasing attention paid to strengths-based reporting models. Such models may, for example, represent topics for which inequalities are understudied, such as indicators for resilience. The focus then moves beyond the problems or deficits inherent in inequality monitoring, which can contribute to stigma Footnote 82 .

Further, selected outcomes are aligned with federal and international quality of life frameworks Footnote 83 Footnote 84 . Accordingly, the report does not represent an exhaustive measurement of positive mental health, but rather a summary of select key indicators.

The mean life satisfaction outcome is based on respondents’ rating of “satisfaction with life as a whole right now” on a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 represents “very dissatisfied” and 10 “very satisfied.” Life satisfaction analyses excluded data from the 2007 to 2008 survey wave as that wave used a different scale. High self-reported mental health is determined by respondents’ reporting of mental health as “excellent” or “very good” compared to the other options of “good,” “fair,” or “poor.”

Another mental health–related outcome analyzed was unmet need for mental health services, which represents the proportion of people who reported having mental health service needs that were partially met or not met at all versus fully met. This outcome was chosen because it aligned with the qualitative literature research findings. Data for the outcome were not collected consistently across CCHS waves, so data from the 2012 CCHS – Mental Health and the 2022 Mental Health and Access to Care Survey (MHACS) were used instead. Both surveys are nationally representative and are similar in design to the annual CCHS.

The Survey on COVID-19 and Mental Health (2020-2021) was utilized for an exclusive and focused analysis of the socioeconomic impacts of COVID-19 on mental health.

The social determinants of health explored in this report include relative household income, employment status, household food security, race/ethnicity, immigrant status, Indigenous identity, sexual orientation, sex/gender, and sense of community belonging. The same method of concurrence with the qualitative evidence was used to determine these social determinants of health.

Whenever possible, quantitative findings were disaggregated by sex/gender. The CCHS reported on respondents’ sex alone until 2019, when a separate variable capturing gender was introduced. In this report, as in the 2018 Key Health Inequalities in Canada: A National Portrait Footnote 85 , we use the sex variable because of its consistency in reporting on sex and/or gender across the years. The use of this variable is based on the assumption that health inequalities between males and females are often driven by the interconnectedness of biologically and socially determined constructs of gender.

Figures showing the quantitative analyses discussed are in accordance with the section’s subject matter. Further details on the mental health outcomes and social determinants of health are described in the Technical Notes ( https://health-infobase.canada.ca/mental-health/inequalities/technical-notes.html ) . Additional outcomes and social determinants were also analyzed and are available in the accompanying online data tool at https://health-infobase.canada.ca/mental-health/inequalities/data-tool.html (refer to Table 1 for a full list).

Table 1. List of Indicators Available in the Report’s Data Tool

| Outcomes (Indicators) |

|---|

| Access to a regular health care provider |

| Anxiety disorder diagnosis |

| Depression and anxiety symptoms |

| Excellent/very good self-rated mental health |

| Flourishing mental health |

| High life stress |

| Mean life satisfaction |

| Mood disorder diagnosis |

| Poor/fair self-rated mental health |

| Strong sense of community belonging |

| Suicidal attempt |

| Suicidal ideation |

| Suicide plan |

| Unmet need for mental health services |

Table 2. List of Stratifiers Available in the Report’s Data Tool

| Stratifiers (By sex/gender and ...) |

|---|

| Ability to speak official language by geography |

| Access to a health care provider |

| Age |

| Education |

| Employment status |

| First official language spoken by geography |

| Geography |

| Household food security |

| Household income |

| Housing tenure |

| Immigrant status |

| Immigrant status by cultural/racial background |

| Immigration recency |

| Indigenous identity – First Nations (off reserve), Inuit, and Métis |

| Living alone |

| Marital status |

| Multiple jobs |

| Neighbourhood immigration and visible minority concentration |

| Neighbourhood material resources index |

| Occupation |

| Occupational mismatch |

| Race/ethnicity |

| Rural/urban residence |

| Sense of community belonging |

| Sexual orientation |

3.3.1 Measuring Population Mental Health: Canada’s Approach to Surveillance

Gathering information about the mental health of the entire population is crucial for shaping mental health systems and services and fostering overall mental health. As more holistic understandings of mental health have emerged, Canadian mental health surveillance efforts have expanded the range of mental health indicators collected through national social and health surveys Footnote 52 to include measures of mental distress, which may not necessarily correspond with a diagnosis of a mental illness, and of positive mental health. Monitoring both dimensions of mental health, such as mental distress and positive mental health, is important to inform strategies that seek to identify risk and protective factors, such as economic status, community belonging, and social interactions (and inequalities within these) that can support mental health promotion efforts.

Canada has well-established systems for monitoring various states of mental illness, suicide, and positive mental health. The Positive Mental Health Surveillance Indicator Framework tracks a number of positive mental health outcomes, such as self-rated mental health, happiness, life satisfaction, and psychological and social well-being, and their associated risk and protective factors, primarily using data from national health surveys (for example the CCHS) Footnote 35 . The PHAC Suicide Surveillance Indicator Framework provides information on suicide and self-inflicted injury outcomes and their associated risk and protective factors.

The Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System (CCDSS) monitors indicators of mental illness using administrative data. These indicators include the use of health services for mental illness and alcohol- and drug-induced disorders, mood and anxiety disorders, and incidence and prevalence of and mortality from schizophrenia Footnote 86 . PHAC also monitors the prevalence of certain self-reported diagnoses of mental disorders using national surveys such as the CCHS Footnote 87 .

Finally, the HIRI provides comprehensive data on the distribution of positive and negative mental health status in different population groups according to a variety of socioeconomic determinants, which can be used to help advance health equity Footnote 88 .

3.4 Implications for This Report and Public Health Surveillance

To reflect the diversity of definitions and constructs described in Sections 2 and 3, this report and the accompanying online data tool explore social determinants of mental health and outcomes that span the dual continua of mental health, from indicators of positive mental health, such as high self-reported mental health and life satisfaction, to associated behaviours, such as substance use, and mood and anxiety disorder diagnoses and related morbidity.

Reflecting critically on how health outcomes are constructed and defined is a useful exercise for researchers devising Canadian public health surveillance systems. In the qualitative literature review, concepts and definitions of mental health varied widely between studies. While some studies referred to the WHO definition of health as a “state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” Footnote 42 , participants in qualitative research studies rarely referred to any one definition. Instead, they spoke of “stress,” “anxiety,” “distress,” “hardship,” “suffering,” “struggling,” and “difficulty,” among other expressions. This raises questions about whether the mental health measures used in population health surveys are relevant and understood by all respondents. In Section 4 and the Discussion, we focus on people who understand and describe mental health in different ways and how mental health can be discussed more broadly.

4. Findings

4.1 Drivers of Mental Health Inequality in Canada

Using a narrative synthesis, we identified four themes related to the social determinants of mental health and well-being: socioeconomic conditions, racism and discrimination, social and cultural connection, support networks, and sense of community belonging, and access, use, and quality of health care services. We conducted a rapid review of 67 qualitative studies published between 2012 and 2022 that explored the social determinants of mental health and well -being in Canada (refer to the Technical Notes ( https://health-infobase.canada.ca/mental-health/inequalities/technical-notes.html ) for detailed methods). The reviewed qualitative research made explicit use of at least 12 theories and theoretical frameworks or models to explore and explain the systems, structures, and forces that shape the social conditions and inequalities in Canadian society. Among these are intersectionality theory; social ecological theory; critical feminist theory; risk environment frameworks; systemic, structural, and symbolic violence; hegemonic masculinity; employment strain model; minority stress theory; and the social determinants of health framework. Arguably, these theories all have the same main purpose of recognizing the relationship of power and privilege afforded to some rather than to others. Many of these theories provide well-supported explanations of the complex, interrelated, and multilevel processes that can result in mental health inequalities. Each explanation identifies unique structural drivers of inequality that occur at a societal level.

These theories recognize that: 1) multilevel processes shape the distribution of social conditions across society and hence the resulting health inequalities (i.e., from the individual, to interpersonal, community, and societal levels); 2) systems of power shape inequalities in health-determining social conditions; and 3) the need to focus on reducing health inequalities to improve the health status of subpopulations.

The mean life satisfaction outcome is based on CCHS respondents’ rating of “satisfaction with life as a whole right now” on a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 represents “very dissatisfied” and 10 “very satisfied.” The high self-reported mental health outcome is determined based on respondents’ reporting of mental health as “excellent” or “very good” compared to the other options of “good,” “fair,” or “poor.”

We recognize that the scope of our literature search may have influenced the types of studies included, and therefore these themes. To address this potential limitation, we conducted a supplementary search of systematic reviews of the social determinants of mental health inequalities to validate our themes (described in detail in Section 3.2.1).

In this section we demonstrate that positive mental health is not experienced equally by everyone in Canada. We profile inequalities at the population level based on 2 indicators—high self-reported mental health and mean life satisfaction—using data from annual cross-sectional components of the CCHS from 2007 to 2021 (refer to Section 3.3 or Technical Notes ( https://health-infobase.canada.ca/mental-health/inequalities/technical-notes.html ) for more details on the chosen indicators). Definitions adopted for indicators are in Section 3.3.

Positive mental health indicators are particularly important as a relationship has been established between high self-rated mental health and health care utilization Footnote 89 and of elevated risk of chronic disease and death Footnote 90 . In addition, recent studies of the mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic have focused on a variety of positive mental health measures, including life satisfaction and self-perceived mental health Footnote 91 Footnote 92 Footnote 93 .

Positive mental health outcomes such as life satisfaction have been shown to vary across countries. In 2022, people living in Canada described their overall satisfaction with life as 7 on a scale of 0 to 10 (compared to the OECD average of 6.7). A few countries, for example, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, the Netherlands, and Switzerland, had average scores of 7.5 or higher Footnote 94 . At the other end of the scale, low levels of life satisfaction (a score of 4 or lower out of 10) were reported by 6.7% of the population in OECD countries from 2013 to 2020. In Canada, less than 3% of the population reported such low scores Footnote 95 . However, aggregate estimates at a country level do not capture within-country differences between populations groups nor widening or narrowing inequalities through time. Further, different social settings and cultural factors may influence different countries’ residents’ perceptions when grading their life satisfaction, hindering cross-country comparisons in many of the international reports.

Despite Canada’s relatively high level of overall positive mental health (as measured by life satisfaction), it is essential to examine within-country distributional differences (or inequalities). This is particularly important because post-pandemic recovery has raised the need to urgently address health inequalities that may have been exacerbated during and by the pandemic. In this section we provide a portrait of the distribution of positive mental health outcomes across different population groups and/or different determinants of health.

4.1.1 Socioeconomic Conditions: Impacts on Mental Health and Well-Being

Socioeconomic status is an important determinant of mental health across different life stages, in Canada and around the world Footnote 96 Footnote 97 Footnote 98 Footnote 99 . The association between socioeconomic status and mental health is influenced by factors that include lack of access to material and social resources and opportunities, stigma and discrimination, and social inequality Footnote 100 . This association is often described in terms of a dual cycle of financial insecurity and poor mental health (also referred to as a bidirectional relationship). That is, changes in income and material resources directly impacting mental health and conversely, how poor mental health might lead to worsening economic outcomes Footnote 100 Footnote 101 . This cycle can continue across generations. Breaking this cycle requires comprehensive approaches that simultaneously address the structural, systemic, and institutional causes of financial insecurity and an inequitable distribution of wealth as well as poor mental health Footnote 79 .

In this section, we describe changes in mental health inequalities over time related to the social determinants of health. These include socioeconomic position (for example, income level, employment status), daily living conditions (for example, stable and safe housing), and structural drivers (for example, food insecurity and working conditions). Findings also reflect mental health inequalities during, and prior to, the COVID-19 pandemic.

Income

Income, poverty, and material deprivation are linked to mental health, as is a person’s socioeconomic position in terms of their employment status or education, for example Footnote 97 Footnote 102 . Psychosocial stress theories posit that relative deprivation may provoke social comparison and contribute to the development of mental health problems by increasing chronic stress, social isolation, unhealthy behaviours, and low self-esteem Footnote 103 . Socioeconomic gradients in mental health—where outcomes tend to be worse among those with the lowest income, lower levels of educational attainment, and low-skilled occupations and improve gradually up the rungs of the socioeconomic ladder—are well documented in Canada Footnote 85 .

Figure 3.A and 3.B show income gradients in mean life satisfaction and high self-reported mental health prevalence over time among males and females. Income gradients narrowed over time, both before (2017–2019) and during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020 to 2022). In 2007 to 2010, there was an approximate 19 percentage-point difference in high self-rated mental health between those in the lowest and those in the highest income quintiles (19.2 for males and 18.7 for females). In 2014 to 2016, the percentage point difference peaked at 20.7 among males and 21.5 among females. By 2020 to 2022, inequalities had narrowed to 12.2 and 11.2 percentage points for males and females, respectively. Over time, income-related inequality in high self-rated mental health was largely similar among females and males.

For life satisfaction, the reduction in income-related inequality over time, which was more prominent among females than males, reflected both an increase in life satisfaction for those in the lowest income quintile and a decline for the more economically advantaged. The narrowing of absolute income-related inequality in high self-rated mental health over time primarily reflected steeper declines among people in higher income quintiles, especially since 2014 to 2016.

Figure 3.A Trends in mean life satisfaction by sex/gender and household income quintile, population aged 12 years and older, 2009–2022

| Year | Sex | Difference in mean life satisfaction score Lowest (Q1) vs. highest (Q5) income quintile (reference) |

Absolute change (95% CI) | Relative change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009-10 | Male | -0.84 (-0.92, -0.75) | -0.14 (-0.26, -0.02) | -17 |

| 2011-13 | Male | -0.97 (-1.05, -0.89) | ||

| 2014-16 | Male | -1.10 (-1.17, -1.02) | ||

| 2017-19 | Male | -0.84 (0.91, -0.78) | ||

| 2020-22 | Male | -0.70 (-0.78, -0.61) | ||

| 2009-10 | Female | -0.93 (-1.01, -0.85) | -0.40 (-0.51, -0.28) | -43 |

| 2011-13 | Female | -0.96 (-1.02, -0.89) | ||

| 2014-16 | Female | -1.07 (-1.14, -1.01) | ||

| 2017-19 | Female | -0.77 (-0.83, -0.70) | ||

| 2020-22 | Female | -0.53 (-0.61, -0.45) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; Q1, quintile 1 or the lowest income group; Q5, quintile 5 or the highest income group; SD, score difference; CCHS, Canadian Community Health Survey.

Notes:

Mean life satisfaction: reported level of satisfaction with life as a whole right now, on a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 means “very dissatisfied” and 10 means “very satisfied.” Negative values of the life satisfaction score differences (SDs) indicate absolute income-related inequalities in life satisfaction over the full time series. A value of 0 indicates that no difference exists between groups on that mental health outcome at a given time point. Changes in inequality are expressed in both absolute and relative scales between only the first and last time periods.

Absolute change calculation: (SD in 2009–2010)−(SD in 2020-2022).